by Lee Gesmer | Jun 27, 2014 | Copyright

In the end Aereo’s dime-sized antennas and subscriber-specific copies of television broadcasts – its “Rube Goldberg” attempt to find a loophole that would allow it to stream TV over the Internet – were not enough to win over a majority of the Supreme Court.

On June 25, 2014, the Supreme Court held that Aereo’s streaming service violated the exclusive right of copyright owners to “publicly perform” their works. Aereo had used diabolically clever technology (or so the broadcasters claimed) in its attempt to avoid this outcome, which seems very likely to force Aereo out of business.

As I have described in detail elsewhere, Aereo’s system – which would have been unimaginable and cost-prohibitive only a few years ago – relied on thousands of antennas and massive, low-cost hard disk storage. Advances in antenna technology allowed Aereo to assign a separate micro-antenna to each paid subscriber. The plummeting cost of digital storage allowed Aereo to save a separate copy of each broadcast transmission for each subscriber that wanted to save a copy.

Aereo’s argument was that for any singe subscriber this was no different (legally speaking) than accessing a broadcast using a rooftop TV antenna connected to a DVR in the living room. In effect, Aereo claimed, each subscriber had outsourced the antenna and the remote DVR to Aereo’s central facility, and Aereo was no more than an equipment supplier.

And, Aereo argued, nothing was accessed or copied unless the consumer initiated access and decided to watch or save a show. In other words, Aereo didn’t collect TV shows and provide a ready-to-access “TV jukebox” the consumer could choose shows from, à la Netflix. If none of Aereo’s subscribers initiated a copy of the “Barney and Friends,” broadcast at 3:00 a.m. on WNET in New York (one of the plaintiffs in the case), it would never be accessed, saved or streamed by Aereo. It was the “volitional conduct” (an esoteric copyright law buzz-phrase) of the subscriber that caused a copy to be made and transmitted, just as it is the volitional conduct of a library patron that causes a photocopy of a copyrighted work to be made on a library photocopier. Aereo argued that it should be no more liable for what its subscribers do with the equipment than is a library with a copy machine on its premises (libraries are not legally responsible for illegal copying by their patrons).

Further, Aereo argued, the fact that it may have transmitted 10,000 personal copies of a World Cup soccer match didn’t constitute a public performance under the Copyright Act, since each transmission was viewed by only one subscriber, not the “public.”

These arguments were enough to persuade the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York (a court many lawyers view as the most knowledgeable and influential of the federal courts when it comes to copyright law), but it didn’t pass muster with the Supreme Court (although three justices dissented, agreeing with Aereo). The Court was unimpressed with the technological details that had occupied the lower courts that had ruled in favor of Aereo, observing that it “did not see how the fact that Aereo transmits via personal copies of programs” makes a difference under the copyright statute. Likewise, the Court rejected Aereo’s argument that transmitting a performance means to make a single transmission, holding that Aereo was transmitting a performance through a “multiple, discrete transmissions.”

Drawing heavily on Congress’ 1976 amendment to the copyright statute intended to bring cable TV companies within the definition of “public performance,” the Supreme Court concluded by analogy that Aereo’s “is not simply an equipment provider . . . that Aereo’s activities are substantially similar to those of the CATV companies that Congress amended the Act to reach.” And, because the fit between the 1976 law and Aereo’s technology was so imperfect, the Court was forced to fall back on what it described as the “overwhelming likeness to the cable companies targeted by the 1976 amendments” and conclude that the technological differences between Aereo and the cable companies “does not make a critical difference.”

Fundamentally, the Court focused on Congress’ regulatory objectives, and on this basis considered Aereo’s technological system of dedicated antennas and personal copies as “not adequate to place Aereo’s activities outside the scope of the Act,” a conclusion the dissent described as a “looks-like-cable-TV” (or“ guilt by resemblance”) standard that will “sow confusion for years to come” and is “nothing but th’ ol’ totality-of-the-circumstances test (which is not a test at all but merely assertion of an intent to perform test-free, ad hoc, case-by-case evaluation).”

* * *

There is no question that had Aereo won before the Supreme Court it would have been a huge upset, and the fourth estate would be doing somersaults. As it is, the outcome was largely anticipated by the small group of lawyers, academics and commentators that paid close attention to the legal arguments made by each side. While most of us prefer to see David defeat Goliath, it has always seemed unlikely that the networks’ $3 billion-plus annual licensing revenues would be weakened by Aereo or Aereo clones.

However, questions remain over what the Court’s ruling (and reasoning) will mean for the delivery of television programming, cloud computing or service-provider liability. Is the dissent correct when it warns that it “will take years, perhaps decades, to determine which automated systems now in existence are governed by the traditional volitional-conduct test and which get the Aereo treatment. (And automated systems now in contemplation will have to take their chances)”?

The answer to these questions is, of course, that it’s far too early to tell. For better or worse, the Supreme Court was careful to emphasize that its decision was limited to the “technologically complex” system engineered by Aereo: “we cannot now answer more precisely how the Transmit Clause or other provisions of the Copyright Act will apply to technologies not before us.” Even so, the Court was careful to note that its decision didn’t reach remote storage (“cloud locker”) services where consumers are able to store digital copies they “have already lawfully acquired.”

Nevertheless, start-ups involved in the delivery of television programming will have to ask whether they cross the line set by Aereo: are they merely an equipment provider (and not liable for direct infringement) or a cable TV look-alike that falls on the wrong side of the line between legality and illegality?

The Supreme Court did little to help companies answer this question, and there may be real concern that Aereo will discourage investment in alternatives to traditional television programming. One thing that seems certain is that any almost every investor in a television technology company will have to ask whether the business plan passes the “Aereo test,” i.e., is copyright compliant. Remote service DVR (“RS-DVR”) services, in particular, may need to reexamine the legality of their services following this decision. Commentators have already questioned whether Aereo has implications for the legality of in-line streaming and in-line linking of images, and noted that regardless of whether the answer is yes or no, the case is likely to raise litigation costs, and thus indirectly chill innovation.

With respect to non-broadcast TV content — for example, the “cloud computing industry” and “cloud lockers” that were the subject of concern expressed by some Justices during oral argument before the Court — it seems unlikely that there will be any implications, at least in the short term, for the reasons described in my post titled Aereo and the Cloud Before the Supreme Court, written just before the Supreme Court decision was issued. Most cloud services provide access to content they own or license, or store files that consumers have already lawfully acquired, a practice the Supreme Court noted was not impacted by its decision. And, cloud services that host third-party content are largely protected (although not entirely) by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

However, copyright law inevitably lags technological development, creating a seemingly never-ending state of uncertainty over how the law will be applied to new technologies. Indeed, Aereo itself illustrates this – the Supreme Court was called on to apply a statute enacted in 1976 to a technology that could not have been envisioned by Congress until decades later. What unintended consequences Aereo might have for innovation and investment in content-delivery and content-storage technologies yet to be invented or imagined is anyone’s guess.

American Broadcasting v. Aereo, Inc. (June 25, 2014)

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 21, 2014 | Copyright

This is a catch-up post on oral argument in ABC v. Aereo, which was held on April 22, 2014.

The Supreme Court’s 2013-2014 term is almost over, and we can expect to receive the Court’s decision in Aereo on June 23rd or 30th.

A great deal has been written about whether Aereo’s TV -to-Internet service violates the TV networks’ public performance right under the transmit clause of the Copyright Act. By comparison, less has been written about the implications of the case for “cloud computing” and “cloud lockers.”*

*note: the “cloud” is simply a metaphor for data and computing power accessed via the Internet.

When the Aereo case was argued before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in November 2012 the “cloud” was not mentioned once. (transcript) However, by the time the case reached oral argument before the Supreme Court in April 2014 cloud computing — or the implications of a Supreme Court decision in Aereo on cloud computing — seemed to have become the focus of the case. Amicus briefs supporting Aereo predicted dire consequence for cloud computing if the Court ruled in favor of the networks,* and the “cloud” is mentioned more than 30 times in the argument transcript,

*note: For example, one amicus brief supporting Aereo warned of “unintended consequences” and argued that the tests proposed by the networks, their amici and the United States “are unworkable and will endanger the thriving cloud computing industry just as it starts to mature.” (link)

What was the Court’s concern about cloud computing, and how did the attorneys for the parties handle the issue?

While the Supreme Court judges didn’t identify their specific concerns about how a decision for the networks might impact cloud computing, they repeatedly referenced it. For example, at the very outset of oral argument Justice Breyer was so concerned about this issue that he questioned whether it would be easier to remand the case to determine whether Aereo is a cable company subject to a compulsory license in order to avoid addressing “serious problems . . . like the cloud.”

The networks’ attorney urged the Court “not to decide the cloud computing question once and for all today, because not all cloud computing is created equal.” (An argument at least one Justice found unsatisfying). Aereo’s lawyer capitalized on this line of questioning, beginning his argument with the assertion that the networks’ interpretation of the copyright statute “absolutely threatens cloud computing.” He argued that the cloud computing industry was “freaked out about this case” because it had invested “tens of billions of dollars” in reliance on the legal principles Aereo was defending.

The attorney for the United States (which sided with the networks) made the best attempt to respond to the justices’ concerns, explaining that “if you have a cloud locker service, somebody has bought a digital copy of a song or a movie from some other source, stores it in a locker and asks that it be streamed back, the cloud locker and storage service is not providing the content. It’s providing a mechanism for watching it.” In other words, a cloud locker service that provides a user access to copies of copyrighted content that the user already has legally obtained would not violate the public performance right.

The Justices, for their part, did more to confuse matters than they did to clarify the issue. Justice Kagan described a system in which “companies where many, many thousands or millions of people put things up there, and then they share them, and the company in some ways aggregates and sorts all that content” and asked the networks’ attorney how a decision against Aereo would impact such a (presumably illegal) Megaupload-like service. Justice Sotomayor confused matters with her reference to the non-existent “iDrop in the cloud” and her apparent lack of awareness that Roku is not a content provider, but a piece of hardware that allows subscribes to access programming services such as Netflix. Justice Scalia asked a question that suggested he might think HBO (a cable channel) was delivered free over the airwaves, and therefore would be susceptible to re-broadcast by Aereo.

Setting aside the melange of law, fact and misinformation at oral argument of the Aereo case the question remains: what would a ruling against Aereo mean for cloud lockers or the “cloud industry”?

The answer, it appears, is very little, since the key question in any cloud storage/copyright case is likely to be, “who provides the content that resides in the cloud locker”?

There are several possible scenarios: First, most data in the “cloud” is either created or licensed by the provider. Subscribers to the New York Times, Wired Magazine and Netflix stream or download files from the cloud. In each of these and thousands of similar services, the content is owned or licensed by the site, and access is restricted to paying subscribers. A Supreme Court ruling against Aereo will have no impact on this part of the “cloud industry.” A variant on this model is where the user already possesses a copy of a file, and “scan-and-match”* technology allows the user to access files on a centralized database maintained in the cloud. Popular “music lockers” provided by Google, Apple and Amazon are good examples of this hybrid model. Again, a decision against Aereo will not affect this model of cloud computing.

*note: Using “scan-and-match” technologies the cloud service maintains one licensed copy of each song, and “matches” the subscriber’s collection against each song in the database. This avoids requiring the user to upload her library to the service (an often time-consuming process) and eliminates the requirement that the service maintain a copy of each file the user uploads, greatly reducing storage requirements.

Second, where content is uploaded to the cloud by a user or subscriber in the first instance and is universally accessible, the cloud service is protected by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act’s (DMCA) notice and take down provisions.* A popular example of this type of cloud service is YouTube. This model would not be adversely impacted by a decision against Aereo.

note: Although Aereo mentioned the DMCA in passing in its brief to the Supreme Court, it has never argued that it is entitled to immunity under the DMCA safe harbors, seemingly conceding that Aereo is the content provider of the TV shows at issue, not Aereo’s users.

Third, in cases where users upload files that are stored individually (e.g., 10,000 copies of “Stairway to Heaven” uploaded and stored separately), the storage site allows only the person who uploaded the file to access it (so-called user-specific transmissions), avoiding copyright liability under the public performance provision based on a combination of fair use (“space shifting” by the user) and application of the “volitional conduct doctrine” by the cloud service.*

*note: Under the “volitional conduct doctrine” a technology provider is not liable for direct copyright infringement when it provides the means for infringement but that infringement is controlled by the “volitional conduct” of the users. An example would be a copy shop. The difficult question, under this line of cases, is whether the technology provider is sufficiently actively engaged in the process to be liable.

Aereo — which copies over-the-air TV transmissions directly and supplies copyrighted content to its subscribers — fits within none of these models, leaving the Supreme Court plenty of room to conclude that Aereo’s argument that a ruling against it will signal a death knell for cloud computing technologies is little more than a straw man argument. The Court can rule against Aereo while making clear that it has no intent to interfer with cloud-based services that use licensed content or provide storage for content the end-user independently possesses and elects to store in the cloud.

My prediction: the Supreme Court will do exactly that, leaving any “close cases” that may arise in the future for the lower courts to resolve.

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 16, 2014 | Copyright

I am proud to have been a member of the CopyrightX class of 2014. If you have any doubts about the merits of online education, apply to take this course in 2015. You will be pleasantly surprised at how effective this form of education can be.

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 13, 2014 | Copyright

While The Author’s Guild copyright suit against Google Books has received most of the attention on the copyright law front, its smaller sibling – the Author’s copyright suit against HathiTrust – has been proceeding on a parallel track. HathiTrust is a consortium of more than 70 institutions working with Google to digitize the books in their libraries, but a smaller number of books than Google Books (only ten million), and for academic use (including an accommodation for disabled viewers), compared with Google Books’s commercial use.

On June 10, 2014, the Second Circuit upheld the federal district court, holding that HathiTrust is protected from copyright infringement under the fair use doctrine. With respect to full-text search (the most legally problematic aspect of HathiTrust), the Second Circuit held:

- “[T]he creation of a full‐text searchable database is a quintessentially transformative use” because it serves a “new and different function.”

- The nature of the copyrighted work (the second factor under fair use analysis) is “of limited usefulness where as here, ‘ the creative work … is being used for a transformative purpose.’”

- The copying was not excessive since “it was reasonably necessary for [HathiTrust] to make use of the entirety of the works in order to enable the full‐text search function.”

- And lastly, “full‐text‐search use poses no harm to any existing or potential traditional market” since full-text search “does not serve as a substitute for the books that are being searched.”

Citing HathiTrust’s “extensive security measures,” the court rejected as speculative the Author’s argument that “existence of the digital copies creates the risk of a security breach which might impose irreparable damage on the Authors and their works.”*

*note: In an earlier post I discussed the Guild’s argument that Google Books creates the ”all too real risks of hacking, theft and widespread distribution.” As I noted in that post, in describing that risk the Guild leaves nothing to the imagination: “just one security breach could result in devastating losses to the rightholders of the books Google has subjected to the risk of such a breach by digitizing them and placing them on the Internet.” In response to similar arguments in HathiTrust the Second Circuit found that there is “no basis in the record on which to conclude that a security breach is likely to occur.”

HathiTrust is distinguishable from Google Books in one significant respect. Non-disabled users can search the HathiTrust database for content, but unlike Google Books, which displays “snippets” of copyrighted works, unless the copyright holder authorizes broader use the results only show page numbers where search terms appear in a given work.

HathiTrust offers additional features to users with disabilities, who can access complete copies if they can show that they are unable to read a work in print. However, the Second Circuit made short shrift of this issue, holding that “the doctrine of fair use allows the Libraries to provide full digital access to copyrighted works to their print-disabled patrons.”

Even taking into consideration the fact that the non-disabled-access HathiTrust library can be distinguished from Google Books on the grounds that it does not provide “snippets,” it is difficult to see how the outcome will be different in the Guild’s appeal of Google Books. The Second Circuit’s central rationales in support of fair use in HathiTrust — that full-text search is transformative and that the database does not serve as a substitute for the books being searched (the latter factor being true in snippet-enabled Google Books as well as in HathiTrust) — likely foretell the fate of the Google Books case* (link), where the federal district court ruled in favor of Google on similar grounds. (For a full discussion of district court decision in the Google Books litigation, click here).

*note: The Author’s Guild suit targeting Google Books is on appeal to the Second Circuit.

Author’s Guild v. Hathitrust, 755 F.3d 87 (2nd Cir. 2014)

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 11, 2014 | Copyright

The idea behind statutes of limitations is usually straightforward. If someone commits an illegal act, after a certain period of time they can no longer be liable (or prosecuted) for that act. In civil cases the statute of limitations usually begins to run when the injured party knew or should have known of the illegal act. Once that period has passed, the injured party is barred from filing a lawsuit. For example, in Massachusetts the statute of limitations for most tort actions is three years. If you are the victim of a tort (for example, medical malpractice), you must file suit within three years of the act that caused you harm, or you likely are barred by the statute of limitations.*

*note: Like almost everything in the law, there are exceptions and nuances to this.

The U.S. Copyright Act contains a three year statute of limitations (17 U.S.C. Section 507),* but the way in which the statute is applied is different. A copyright holder may know that a defendant has been selling an infringing product for more than three years, but that doesn’t bar an action for copyright infringement – the defendant may still be liable for any infringing conduct taken during the three year period before the suit was filed. This is described as a “three-year look back,” a “rolling limitations period” or the “separate-accrual rule.”**

*note: The statute provides that “No civil action shall be maintained under the provisions of this title unless it is commenced within three years after the claim accrued.”

**note: A new statute of limitations “accrues” (commences) with each new infringement.

In theory, therefore, a copyright owner can become aware of an infringing use of her work and do nothing for an indefinite period of time – more than just three years – until, for example, she concludes that the infringer has earned profits that could be recovered as damages and therefore justify the cost of a lawsuit. At that point the copyright owner can file suit and the statute of limitations will come into play, but only to limit damages to the preceding three year period. However, if the copyright owner wins her case and the defendant doesn’t settle there is the possibility that the copyright owner will wait three years and then file another infringement suit based on infringing actions taken during the second three year period. And so on, ad infinitum (or so it will seem to the defendant, given the length of copyright protection).

Until recently infringers were not wholly at the mercy of this strategy. They were able to raise the common law legal doctrine of “laches,” a doctrine which may bar a lawsuit based on an unreasonable, prejudicial delay in commencing suit. In many cases defendants successfully arged that a copyright owner should not be permitted to wait beyond three years before filing an infringement suit.

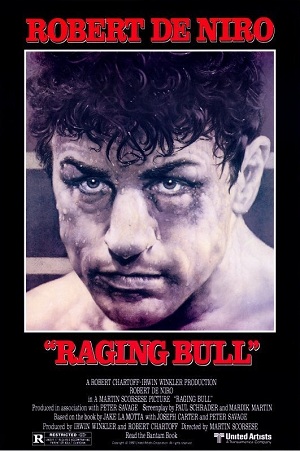

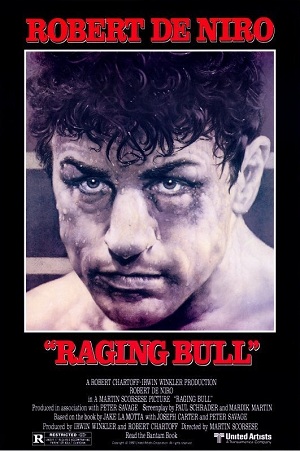

These two legal principles — the three-year copyright statute of limitations and the laches doctrine — came into collision when Paulla Petrella brought a copyright suit against MGM. Since 1981 Petrella has been the heir to her  father Frank Petrella’s copyright interest in a book and two screenplays about the life of Jake LaMotta, the central character portrayed in the film Raging Bull. She asserts that Raging Bull is a derivative work of the book and screenplays, and that she is entitled to royalties based on MGM’s distribution of the film during the three years preceding her suit.

father Frank Petrella’s copyright interest in a book and two screenplays about the life of Jake LaMotta, the central character portrayed in the film Raging Bull. She asserts that Raging Bull is a derivative work of the book and screenplays, and that she is entitled to royalties based on MGM’s distribution of the film during the three years preceding her suit.

Ms. Petrella had threatened MGM with a suit for copyright infringement as far back as 1998, but she didn’t actually file suit until 2009. In fact, Raging Bull was released in 1980, and there is evidence that Ms. Petrella was aware of her copyright infringement claim as far back as 1981, in which case she delayed for almost 30 years before filing suit for copyright infringement.

MGM raised the defense of laches, and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, dismissing the suit. The Supreme Court took the case and reversed in a 6-3 decision, holding that, except in “extraordinary circumstances,” laches cannot be invoked to preclude a claim for damages that falls within the three-year window. However, this was not a clear win for Petrella or others in her position: oddly, the Court held that delay is relevant to equitable relief which (the Court stated), includes not only an injunction against further public display or distribution of the copyrighted work, but also damages based on the infringer’s profits that are attributable to the infringement.

Whether this decision leads to a flood of hitherto dormant copyright suits remains to be seen, and may be influenced by how the lower  courts interpret and apply the decision. For example, given the Supreme Court’s comments it is uncertain that Ms. Petrella will be able to obtain an injunction against future sales of Raging Bull, and the Court’s statement that a delay in bringing suit is relevant to determining damages based on MGM’s profits during the three year period may limit any recovery by allowing MGM to use its investment in the film prior to the three-year look-back period to offset profits earned during those three years. Therefore, the extent of any potential monetary recovery is unclear.

courts interpret and apply the decision. For example, given the Supreme Court’s comments it is uncertain that Ms. Petrella will be able to obtain an injunction against future sales of Raging Bull, and the Court’s statement that a delay in bringing suit is relevant to determining damages based on MGM’s profits during the three year period may limit any recovery by allowing MGM to use its investment in the film prior to the three-year look-back period to offset profits earned during those three years. Therefore, the extent of any potential monetary recovery is unclear.

*note: Although, as discussed above, assuming Petrella establishes liability (an issue yet to be addressed in this case) and MGM continues to distribute the film, in theory Petrella could file a series of lawsuits every three years seeking MGM’s profits for the preceding three year period. After the first suit MGM would be on notice that it is exploiting a copyright-protected work, and would likely have little choice but to to settle the case, rather than have this sword of Damocles hanging over its head.

Many observers in the copyright community think that Petrella may lead to a wave of lawsuits by copyright holders who had assumed, until now, that their claims might be barred by laches. A prominent example suggesting this may be the case is the May 31, 2014 lawsuit filed by the Randy Craig Wolfe Trust against the members of Led Zeppelin. Wolfe, the deceased founder and creative force behind the band Spirit, had believed since the mid-’90s (and perhaps as far back as 1971) that the intro to Stairway to Heaven had been copied from Taurus, a song on a Spirit album released in 1968. It seems unlikely that this case, filed less than two weeks after the Petrella decision, was not encouraged by the outcome in Petrella.

Petrella could also have implications for application of the laches doctrine under patent law. As the Supreme Court noted in Petrella, the Federal Circuit has held that laches may be used to bar patent damages prior to the actual commencement of suit. The courts may conclude that the rationale of the Supreme Court in Petrella applies under the patent statute as well, making it easier for patent plaintiffs to take advantage of the full six year statute of limitations under the patent statute.

Petrella v. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc., No. 12-1315 (May 19, 2014)

Scotusblog page on Petrella

father Frank Petrella’s copyright interest in a book and two screenplays about the life of Jake LaMotta, the central character portrayed in the film Raging Bull. She asserts that Raging Bull is a derivative work of the book and screenplays, and that she is entitled to royalties based on MGM’s distribution of the film during the three years preceding her suit.

father Frank Petrella’s copyright interest in a book and two screenplays about the life of Jake LaMotta, the central character portrayed in the film Raging Bull. She asserts that Raging Bull is a derivative work of the book and screenplays, and that she is entitled to royalties based on MGM’s distribution of the film during the three years preceding her suit. courts interpret and apply the decision. For example, given the Supreme Court’s comments it is uncertain that Ms. Petrella will be able to obtain an injunction against future sales of Raging Bull, and the Court’s statement that a delay in bringing suit is relevant to determining damages based on MGM’s profits during the three year period may limit any recovery by allowing MGM to use its investment in the film prior to the three-year look-back period to offset profits earned during those three years. Therefore, the extent of any potential monetary recovery is unclear.

courts interpret and apply the decision. For example, given the Supreme Court’s comments it is uncertain that Ms. Petrella will be able to obtain an injunction against future sales of Raging Bull, and the Court’s statement that a delay in bringing suit is relevant to determining damages based on MGM’s profits during the three year period may limit any recovery by allowing MGM to use its investment in the film prior to the three-year look-back period to offset profits earned during those three years. Therefore, the extent of any potential monetary recovery is unclear.