Many people who’ve lived with the traditional rules of intellectual property during their professional lives are struggling with non-fungible tokens, or “NFTs”. I’m one, and it’s a bit of an existential crisis for us. My advice – relax and repeat after me: “this has nothing to do with copyright law.”

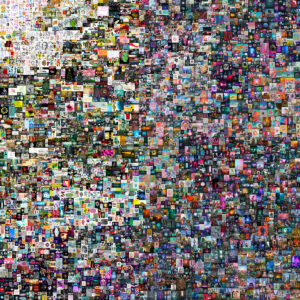

The existence of NFTs came to the attention of many people after Christie’s sold Beeple’s Everydays: the First 5000 Days – a collage of 5000 digital art images – for $69 million in early 2021. One of the 5000 images is at the top of this post. The purchaser was Vignesh Sundaresan, and to be precise, Sundaresan purchased this NFT in exchange for $69 million worth of Ether cryptocurrency.

What, I asked when I first heard this, did the buyer receive in exchange? I assumed the buyer received copyright title in the artwork. Or perhaps a license to the work. This was a copyright transaction involving digital art, right? Old wine in new bottles.

Wrong!

Although the subject matter of the Beeple NFT appeared to fall in the realm of copyright law – digital artwork – Mr. Sundaresan received none of these things, nor anything else that one would associate with copyright law.

Warning, blockchain jargon ahead: Mr. Sundaresan received a unique (hence “non-fungible”) crypto “token” – not to be confused with non-unique (hence “fungible”) cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum that can be traded on a blockchain. His purchase of this NFT was subject to a “smart contract” that you can read here (2,000+ lines of code, good luck). The token is managed (recorded, bought/sold) on a public blockchain, a decentralized, peer-to-peer network-based digital ledger system that tracks the ownership of the NFT. The token contains a link to a location on the Internet that holds a copy of the digital artwork, but there was no transfer of ownership of the artwork. Christie’s terms of sale made this clear to potential purchasers.

Let me stop now and note that, based on my reading on the subject, there’s a lot of confusion around NFTs, even among the Internet 3.0 cognoscenti. A photo or musical work created today is under copyright, and the owner (often the author, particularly in the world of NFTs) can control reproduction and public display/performance. In the world of traditional copyright transactions a buyer owns the physical copy s/he purchases. If there’s only one copy, or a limited series, the original may increase in value – this is why people invest in art.

By contrast the buyer of an NFT rarely (if ever) acquires ownership of the art work. And here we see the copyright conundrum – historically, no knowledgeable art investor would spend a large sum of money to buy a piece of digital art to which they didn’t own the copyright or a physical copy, and which could be reproduced and downloaded off the Internet with the right-click of a mouse.

This is the “legal” aspect of NFTs that leaves intellectual property lawyers perplexed – in many instances the seller of the NFT makes no promises, other than not to resell the specific NFT purchased by the buyer. The buyer owns nothing more than a fragment of code that exists on a blockchain, and a link to a website that holds an authentic copy (one hopes) of the artwork.

The point is this: in the world of NFTs – which typically involve artwork, video and music – purchasers of NFTs do not obtain any intellectual property ownership in the work associated with the NFT unless it is explicitly transferred. In the case of Beeple’s artwork, the buyer didn’t purchase the artwork and he didn’t purchase the copyrights – the buyer purchased the token, and the right to hold or resell it. The images in Beeple’s $69 million collage are all freely available on his website.

Now, lawyers, wake up! There’s good news for you. NFTs may be subject to “smart contracts.” What is a smart contract? It’s a computer program executed in the blockchain by algorithmic code when given certain data. You can see the Beeple contract linked above (the MakersTokenV2 standard), and another example here (the ERC721 standard). If you have the courage to click through you’ll see that these so-called “contracts” look nothing like traditional contracts – they are computer code.

However, with smart contracts traditional legal principles have infiltrated the world of NFTs – at least to the extent that a court can “translate” and enforce a code-based contract. The buyer and seller of the NFT can agree to copyright-like rights, either on the blockchain or even in a traditional “off-blockchain” natural language contract. They could also agree, for example, that if the token is resold a percentage of the resale price would be paid to the NFT creator, or some other third party (perhaps a charity). The smart contract would cause this to occur automatically and the designated recipient would receive payment in crypto currency without any human intervention.

So, to return to my original point – at first this is all a bit mind boggling to people steeped in traditional copyright law, but not so much if you understand that NFTs often involve works that could be the subject of traditional copyright transactions, but aren’t.

If you’ve been paying attention and think you’ve understood everything I’ve said, you may still feel confused. Don’t feel badly, almost everyone else is too. If you’d like to read further on this topic I recommend Deconstructing that $69million NFT (explaining what an NFT is, in technical detail) and the October 26, 2020 episode of the 4PC Podcast, which explains some of the legal issues involved with smart contracts.

If you still aren’t sure what an NFT is, or why people are willing to pay huge sums of money for them, I’ll leave you with copyright lawyer Rebecca Tushnet’s explanation. When asked to explain the value of a NFT she responded –

The value is the ability to say that you own the NFT. Like blockchain currency, it is worth whatever humanity collectively or individually decides it’s worth. It is a melding of Oscar Wilde and Andy Warhol, art for art’s sake and commerce for commerce’s sake.