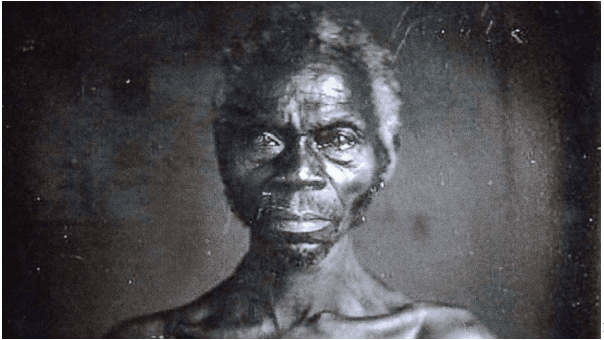

Louis Agassiz thought that black and white races had different origins. In 1850 Agassiz – an eminent professor at Harvard – embarked on a tour of South Carolina plantations in search of racially “pure” Africans whom he could study as evidence to support this theory, known as “polygenism.”

On the trip Agassiz commissioned a photographer to take daguerreotypes of Renty Taylor and his daughter Delia, two slaves who lived on a South Carolina plantation.

The images – believed to be the earliest photos of American slaves – disappeared into the archives of Harvard’s Peabody Museum for over a hundred years, only to be discovered by a museum employee in the 1970s and widely publicized by Harvard.

In 2011 Tamara Lanier learned she was a descendant of Renty and Delia and became aware of the daguerreotypes. She wrote to then-Harvard President Drew Faust and asked that Harvard give these family artifacts to her. To make a long story short, Harvard declined. In the words of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) Harvard was “dismissive” and “disrespectful” when it wasn’t ignoring her altogether.

Represented by celebrity civil rights lawyer Ben Crump and others Lanier sued Harvard. She didn’t want money – she wanted Harvard to give her the daguerreotypes.

Lanier’s claim had nothing to do with the images, which are unprotected by any copyright. Lanier asserted a property right. She wanted the physical daguerreotypes – the copper plates – that were created in 1850 and which Harvard had retained for almost 175 years.

Harvard refused and Lanier sued. Lanier’s suit contained a variety of legal claims, but the central claim was for “replevin.” Replevin is a legal right that has a thousand year history in British and U.S. law. Replevin enables someone to regain possession of property that belongs to them. If you steal my bicycle and refuse to return it I could go to court and file an action for replevin to force you to hand it over. This is what Lanier wanted – to force Harvard to give her the physical media that held the images of her ancestors.

Her suit failed, although the court did throw her a bone – it held that Louis Agassiz’s actions in 1850, and Harvard behavior toward Ms. Lanier post-2011, were plausibly extreme and outrageous, and therefore might support claims of intentional and reckless infliction of emotional distress. The case could proceed to trial on these theories.

However, these claims appear to be little more than an afterthought – they aren’t mentioned in the appellate briefs or oral argument before the SJC. While Ms. Lanier is pursuing them post-appeal they are unlikely to yield much in the way of money, and they won’t give her the relief she was seeking.

Why did the SJC deny her property claim? The SJC’s decision in this case is a remarkable deep dive into the history of slavery and racism in 19th Century America. The Harvard professor, Louis Agassiz, was not an obscure academic – he was a giant in the study of natural history, and geology. Until not long ago a neighborhood in Cambridge, Massachusetts where he had lived was known as “Agassiz.” Reading the legal filings and the SJC decision is as much a historical journey through American slavery and a moral crusade as a legal argument. The central message is that Harvard committed a terrible wrong to Renty and Delia in 1850, and that Harvard’s refusal to give his ancestors the daguerreotypes is a continuation of that wrong. In essence, Lanier asked Harvard to do the right thing and give the plates to her. When Harvard refused to do so Lanier’s lawyers asked the courts to force Harvard to compel Harvard to do the right thing.

Lanier’s arguments failed before the SJC. The court held that Lanier was unable to satisfy the strict requirements of replevin because she had no property interest in the plates. Under well-established law the photographer (or in this case the commissioning party, Harvard) owns the negatives from a photograph. The court declined to make “new law” that would give her possession of the plates. And, in any event, her claim was barred by the statute of limitations.

One of the seven SJC justices – Associate Justice Elspeth Cypher – wrote separately and argued for a new common-law cause of action. In a concurring opinion she argued that the common law may be used to remedy any injustice. While she cited many case decisions that support this proposition, the most powerful statement came from former SJC Chief Justice Ralph Gants:

“We are responsible [for] and the sole arbiter of the common law of Massachusetts. The common law of Massachusetts is ours. We are responsible for it. . . . probably the single most important thing … is that it is our obligation to correct miscarriages of justice. . . . we don’t walk away from miscarriages of justice. We don’t generally say, `well, we rely upon the importance of continuity, so if it was an injustice that occurred a while ago, we’re just going to leave it be.’ Our obligation is to correct a miscarriage of justice whenever it happens, and that is part of what is bred in our bone.”

R.D. Gants, C.J., Welcome Remarks (Aug. 31, 2020).

Tragically, Justice Gants passed away suddenly in 2020, just a month after making these remarks, so he had no voice in the SJC’s Lanier decision.

Justice Cypher proposed an extraordinarily narrow legal legal test to resolve this case – a test that might provide justice to Ms. Lanier and likely never be applied again:

“a plaintiff must show that (1) she is a direct lineal descendant of a specific individual or individuals enslaved in the United States or in a colony that later became a part of the United States; (2) the defendant has possession of an artifact, which was created or obtained as a consequence of the enslavement of the plaintiff’s ancestors; (3) the defendant participated, either directly or indirectly, in the wrongful creation or attainment of such artifact; (4) the artifact provides a meaningful connection between the plaintiff and her ancestors; and (5) the plaintiff has made a request or demand to the defendant to relinquish the artifact to the plaintiff, which the defendant has refused or ignored. On establishment of the foregoing elements, as the sole remedy for this cause of action, the plaintiff would be entitled to the specific performance of transfer of possession of the artifact from the defendant to the plaintiff.”

The majority of the Court rejected this test, arguing that –

“we can identify no support in the common law of this Commonwealth or any other State for the new cause of action that Justice Cypher’s concurrence would create to allow descendants of persons who were enslaved to obtain possession of artifacts that resulted from the enslavement of their ancestors. . . . the new right proposed in Justice Cypher’s concurrence does not derive from common-law reasoning, which is a precedent-based, evolutionary decision-making process providing both for continuity and change. Rather, a right and remedy, without precedent, would be created anew.”

As best I can determine, Ms. Lanier has no further legal recourse. There are no federal constitutional or statutory issues in the case, so she has no right of appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. Unless Harvard has a change of heart, Harvard will maintain possession of the daguerreotypes of Renty and Delia Taylor in perpetuity.

Lanier v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, 490 Mass. 37 (2022)