by Lee Gesmer | Oct 26, 2023 | Copyright, General

By Lee Gesmer and Andrew Updegrove

Every citizen is presumed to know the law … and it needs no argument to show… that all should have free access to its contents.

U.S. Supreme Court in Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org (2020)

Many private organizations promulgate best-practice standards. Two examples you might be familiar with are the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM).

In the U.S., unlike most foreign countries, standards are developed “from the bottom up” by the private sector, rather than “from the top down” by government agencies or quasi-public bodies. In keeping with this division of labor, government agencies have come to rely extensively on private sector standards developers to provide standards suitable for adoption as regulations.

Federal law permits federal agencies to incorporate privately developed standards into law by referencing them in the Federal Register without reproducing them there. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) has more than 27,000 incorporated standards. States and municipalities do this as well, adding to that number. Once adopted the standards carry the force of law.

These private-government relationships are crucially important – they leverage specialized knowledge and industry expertise to formulate robust and reliable standards that the government could not create by itself, and save untold millions of tax dollars in avoided costs for government agencies that would otherwise have to generate them. The standards organizations that provide standards referenced into law, in turn, gain legal legitimacy and wider application for their standards.

There is also a commercial side to these relationships – many standards organizations support themselves in part by the sale of their standards.

Public.Resource.Org (Public Resource) is a nonprofit group that disseminates legal materials. Its website has posted thousands of standards, including those produced and copyrighted by ASTM. ASTM (along with two other standards organizations) sued Public Resource for copyright infringement. The case has been working its way through the courts for a decade. Absent a successful appeal to the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia finally decided the issue on September 12, 2023. It held that the non-commercial dissemination of these standards as incorporated by reference into law constitutes copyright fair use, and therefore cannot support liability for copyright infringement.

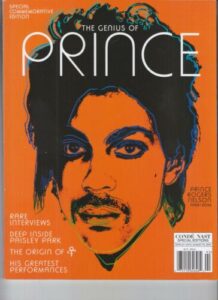

As we have observed on many occasions, copyright fair use is an unpredictable legal doctrine. Often, the outcome seems to be in the eye of the beholder – the judge or judicial panel – rather than the result of any predictive legal test. A recent example of this is Goldsmith v. Warhol: a federal district court held that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo of Prince was fair use. The Second Circuit reversed, holding that it wasn’t. The Supreme Court upheld that ruling, but under a different rationale from the Second Circuit. Three courts, three different approaches to fair use. For another example see Final Thoughts On Google v. Oracle. The result is a confusing body of law that lacks predictability for the copyright community, both authors and the lawyers that are asked to advise them.

D.C. Circuit’s Holding in ASTM

While Warhol involved art and Oracle software, ASTM involved privately developed technical standards that had been incorporated into law “by reference.”

There is no question that in most cases technical standards are copyrightable – that is, they reflect sufficient originality to be protected by U.S. copyright law. Hence, without an affirmative defense Public Resource’s reproduction and distribution of ASTM’s standards infringed its copyrights. Public Resource’s defense was copyright fair use.

The D.C. Circuit applied – as it must – the four-factor fair use test:

Purpose and Character of the Use. Under the first factor it found that the “purpose and character“ of Public Resource’s nonprofit status favored fair use. Further Public Resource’s use of the standards – to provide a free repository of the law – is “transformative,” a key issue in any fair use case. While in most cases the term “transformative” involves changes to the work, here the court construed it to mean a transformative “use” of the work.

Nature of the Copyrighted Work. Factor two also favored fair use. Because the court viewed the standards as “factual” in nature – a conclusion we find questionable – it conclude that they “fall at best, at the outer edge of copyright’s protective purposes.” Factual works are often given “weak” or “thin” copyright protection, and because protection is weaker for such works, it’s easier to establish fair use.

Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used. Under factor three, although Public Resource copied the standards in their entirety, the court found that this was necessary in light of the purpose. “If an agency has given legal effect to an entire standard, then its entire reproduction is reasonable in relation to the purpose of the copying . . ..” This is not unusual in the context of copyright fair use – many fair use cases involve comprehensive copying. Oracle is a good example of this.

Effect of the Use Upon the Potential Market for or Value of the Copyrighted Work. Lastly, the fourth fair use factor required the court to consider the “market harm“ caused by Public Resource’s copying, including any substantially adverse impact on the “potential market“ for the original standards. While the court observed that it “seems reasonable” to suppose that economic harm might result, it found that the plaintiffs could not quantify past or future financial harms, relying instead on “conclusion, assertions and speculation.“ In any event, even if Public Resource’s free postings lowered the demand for the plaintiffs’ standards, this was outweighed by “the substantial public benefits of free and easy access to the law.“ The court concluded that the fourth fair use factor did not tip the balance one way or the other. But because the first three factors “strongly“ favored fair use, it found that Public Resource’s non-commercial posting of standards incorporated into law by reference is fair use.

Legal Precedents Favored Public Resource

The extent to which the law should be in the public domain is not a new issue for copyright law. In 2020 the Supreme Court held that annotations to Georgia’s official statutory code, as government edicts, were free from copyright. In that case the Court didn’t even reach fair use – it held that officials who “speak with the force of law” cannot claim copyright in the works they create in the course of their official duties.” Georgia v. Public Resource.

The lower courts have also weighed in on this issue. In Veeck v. Southern Building Code the Fifth Circuit relied on fair use to hold that model building codes adopted by reference could be copied. In Building Officials & Code Administration. v. Code Technologies, Inc. the First Circuit suggested that once a model building code has been adopted into law it is in the public domain, and remanded for further consideration.

Public Resource relied heavily on these cases on appeal, and indeed, these precedents put ASTM and its co-plaintiffs in an uphill battle heading into the appeal to the D.C. Circuit.

Copyright Fair Use Based On “Public Benefits”

While not explicitly identified in the Copyright Act, the “public benefit” theory of fair use prioritizes societal and cultural benefits in the application of copyright law. A recent example of this is the Supreme Court’s holding in Oracle v. Google. In this 2021 case the issue was whether Google’s use of Oracle’s Java API (Application Programming Interface) in its Android operating system constituted fair use. While Google copied all of Oracle API and used it commercially, the Court found fair use, based in part on the benefit to the software development industry and technical innovation. As the Court said, “we must take into account the public benefits the copying will likely produce.”

Similarly, in the 2015 Google Book Search decision, Author’s Guild v. Google, the Second Circuit recognized the substantial public benefits of Google’s project in concluding that Google’s verbatim copy of books was protected by fair use.

The D.C. Circuit’s ruling in the ASTM case follows this line of reasoning. Just as there is a public benefit in allowing software developers to use the Java API, and a public benefit in allowing the public to search copyright-protected books for relevant “snippets,” so does the publication of laws incorporated by reference benefit the public by making the law more accessible. However, as we discuss below, it did this at the risk of upsetting the delicate balance between the standards organizations and the governments that benefit from their works.

Was the “Public Benefits” Theory of Fair Use Properly Applied in ASTM?

While the D.C. Circuit’s holding allowing the unauthorized reproduction of standards may fall within the “public benefits” line of fair use cases, in our view there is a risk that the court misjudged the interplay between standards organizations, government entities, and public access. Any challenge to the delicate symbiotic private-government relationship risks injury to the public interest, which benefits from the creation of these standards. Based on our experience working with nonprofit standards organizations for decades, we fear that the D.C. Circuit underestimated this potential disruption.

Importantly, the court found insufficient an accommodation that many standards developers (including ASTM) have already put in place in response to Public Resource’s challenge. Specifically, they have created public “reading rooms” where every standard they have developed that has been incorporated into law by reference can be read, free of charge, online in read-only mode. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) hosts an “IBR Standards Portal” offering one stop access to the incorporated by reference (IBR) standards of a dozen major standards organizations can be accessed, as well as links to another sixteen standards organizations reading rooms with links to their own IBR’d standards.

As noted, many standards organizations charge a fee for copies of their standards. In the case of many traditional standards developers, such fees comprise a major, or even the majority, of the budgets of the organizations. Developing standards is inherently time-consuming and expensive, and in some cases (e.g., organizations that develop building codes), most or all of the production of such organizations is referenced into law. In other cases, standards were never intended for referencing into law, but have been nonetheless, without notice to, or consent by, the organization that developed them. The revenues from sales and licensing are reinvested into research, development, and enhancement of new and existing standards. Respecting copyright protects the investments of these organizations in developing standards, ensuring they can fund their continuing operations and standards development and providing incentives to continue to create these essential public goods.

The unauthorized distribution by nonprofits risks reducing those revenues and incentives by offering a free alternative to purchasing or licensing the standards. This, in turn, risks slowing down the frequency of updating existing standards and innovating new ones, potentially leaving them outdated or less applicable to evolving industry needs.

This may prove to be the case if the implications of the decision extend beyond nonprofit vendors to for-profit companies. Some for-profit companies already do sell copies of standards without first paying for the rights to do so. It is difficult to see how the court’s rationale – finding fair use when a nonprofit engages in this behavior – does not extend to for-profit sales of standards.

Our bottom line takeaway: the implications of this decision on private standard-setting organizations and their business models may be far reaching. Hopefully, there may be a legislative solution that may provide relief. On March 17, 2023, Darrell Issa (R CA) introduced proposed amendments to amend the Copyright Act with bipartisan support from seven representatives from each party. If enacted, the bill would void a fair use defense against a claim of infringement of an IBR’d standard if that standard “is displayed for review in a readily accessible manner on a public website,” without cost.

We support this common sense ratification of the public reading room approach and hope that the bill is adopted.

American Society for Testing and Materials v. Public.Resource.Org., Inc. (D.C. Cir. Sept. 12, 2023).

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 28, 2023 | Copyright

In an previous post I focused on the AI “output” issue – who owns an AI model’s output? (Artificial Intelligence May Result In Human Extinction, But In the Meantime There’s a Lot of Lawyering To Be Done). I noted that this issue was pending in a lawsuit before the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia (Thaler v. Perlmutter).

The decision in this case was issued by Judge Beryl A. Howell on August 18, 2023. In her ruling Judge Howell made it clear that a creation born out of an artificial intelligence system cannot be copyrighted due to the lack of human creativity, the “sine qua non at the core of copyrightability.”

Background

In 2019 Stephen Thaler filed an unusual copyright application. Instead of a traditional artwork, the piece – titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” (the image appears at the top of this post) – identified an unusual ‘creator’ – the “Creativity Machine.” The Creativity Machine is an AI system invented by Thaler. In his application for registration Thaler informed the Copyright Office that the work was “created autonomously by machine,“ and his claim to the copyright was based on the fact of his “ownership of the machine.“

The Copyright Office, however, didn’t see it his way. Its position is that that copyright protections are reserved exclusively for works born from human ingenuity. See Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence. On this basis it declined Thaler’s application.

Judge Howell’s Decision

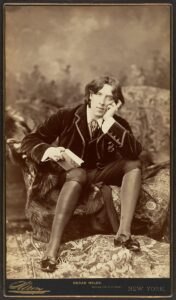

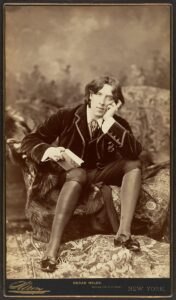

Oscar Wilde photo in Burrow-Giles case

On appeal to the district court Judge Howell acknowledged that copyright law is “malleable enough to cover works created with or involving technologies developed long after traditional media.” A prime example of this is the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1884 decision in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, holding that a photograph of Oscar Wilde was copyrightable despite use of a camera, since the camera was used to give “visible expression” to “ideas in the mind of the author.” However, the rationale in this case didn’t go far enough for Judge Howell. Her decision emphasized the foundational principle of copyright: human creativity –

The act of human creation—and how to best encourage human individuals to engage in that creation, and thereby promote science and the useful arts—[has been] central to American copyright from its very inception. Non-human actors need no incentivization with the promise of exclusive rights under United States law, and copyright was therefore not designed to reach them.

The Copyright Act itself leans heavily toward human-centric creation, with previous court decisions strengthening the court’s perspective. The case that has received much of the attention on this topic is Naruto v. Slater, where a photograph, though artistically noteworthy, wasn’t given copyright protection because it was taken by a monkey, not a human – “all animals, since they are not human,” lack standing under the Copyright Act.

Attempting to navigate this legal maze, on appeal Thaler presented a fresh angle. He argued that as the mastermind behind the AI, providing it with direction and instructions, he should be considered the rightful human author. But this theory had not been asserted in his original application for registration, and therefore was dismissed by the court: “here, plaintiff informed the register that the work was ‘created autonomously by machine,’ and his claim to the copyright was only based on the fact of his ‘ownership of the machine.'” Therefore, the court limited Thaler’s appeal to the question of whether a work generated autonomously by a computer system is eligible for copyright, and held that it was not.

Navigating Uncharted Waters: Future Implications

9th Cir in Naruto case: Monkey selfie not copyright-protected

The Thaler case sets a precedent: a creation made entirely by an AI, without human intervention, remains outside the protective bounds of the Copyright Act – at least for now. Not surprisingly, Thaler has announced that he will appeal this ruling to the D.C. Circuit. Onward and upward.

Moreover, this case leaves unaddressed a myriad of yet-to-be-answered questions:

- At what point, and to what extent – if at all – does human interaction with AI validate a creation as human-made?

- How do we gauge the originality of AI creations when these AI systems might have been trained using pre-existing works?

- Should the current structure of copyright be reformed to support and foster AI-involved creations?

These questions remain tantalizingly open, awaiting future exploration and legal interpretation. The ongoing debate about AI’s role in the world of creativity and copyright is just beginning.

Thaler v. Perlmutter (D. C. August 18, 2023)

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 15, 2023 | Copyright

A couple of people have asked me about the legal story behind Taylor Swift’s re-recording of her earlier albums.

Great question. In fact, she has re-recorded three of them.

This unusual story is a perfect “music copyright” teaching moment.

Why The Re-Recordings?

The background is a bit convoluted, but it arises out of an ugly split between Swift and her first recording company, Big Machine Records. Following the split Swift began releasing her re-recorded songs, Fearless (Taylor’s Version) and Red (Taylor’s Version) in 2021 and Speak Now (Taylor’s Version) in 2023.

Why did she re-record the songs on these albums? The gory details are discussed under the link above, but after the falling out with Big Machine, Swift decided to re-record the songs owned by it, apparently with the intention of diverting sales from her former recording company.

Swift’s popularity and financial resources allow her to do something few other artists could hope to undertake.

Copyright Law and Music

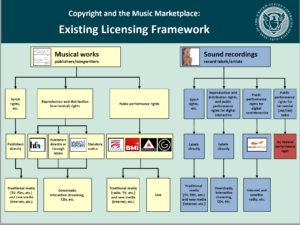

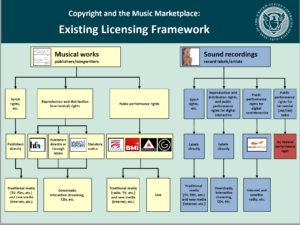

There is an important aspect of copyright law at the heart of what happened here. Every musical recording potentially has two copyrights – one in the musical work and one in each recording of the work. The musical work is the composition – the chords, melody and lyrics. Swift penned the songs on these three albums and as the author, retained ownership of these musical works. However, she assigned the recordings or “masters” to her recording company. Although she might earn royalties based on the sales and performances of these masters, she doesn’t own the copyright for them.

By not also assigning ownership of the musical works represented by the songs on the three albums, Swift retained what the music industry refers to as “publishing rights,” as in “hey, I own the publishing for this song, right?” Swift is therefore free to re-record them, as she has now done in the three “Taylor’s Version” albums.

Further Intricacies and Questions

It’s likely that there’s more to this story than has been revealed to the public. For instance, a contract between Swift and Big Machine may have temporarily delayed Swift from re-recording her songs. However, that’s more about contract law than copyright. The music industry, often a confusing maze, juggles both copyrights and contracts.

It’s likely that there’s more to this story than has been revealed to the public. For instance, a contract between Swift and Big Machine may have temporarily delayed Swift from re-recording her songs. However, that’s more about contract law than copyright. The music industry, often a confusing maze, juggles both copyrights and contracts.

The extent to which Swift is getting her hoped-for revenge is unknown – we don’t know the extent to which the re-recordings are cutting into sales of the original masters. And, no doubt there are many other legal complications that have not been made public. For example, assume a movie producer wants a “synchronization license” (a “sync” license) to use one of these recordings with a movie or TV show. The producer needs a license to both the master and the musical work. I can imagine Taylor Swift saying, “if you want a license to the musical work you need to license the new master from me as well.” This would cut out the owner of the first recording, and no doubt lead to threats of contractual interference. But is it legal? It probably is.

When I introduced the distinction between the copyrights in musical works and masters above, I said that “every musical recording potentially has two copyrights.” Why did I say “potentially”?

An example will illustrate why. Assume that in 2023 a symphony orchestra records and releases a performance of Antonín Dvořák’s NewWorld Symphony, composed in 1893. The copyright in the musical work has expired. Anyone is free to record this work. However, a new copyright applies to the new recording and will last for decades. Thus, only one copyright – the copyright in the master – exists in this scenario.

If you’re interested in the drama between Taylor Swift and her former record company, this Wikipedia entry has most of it.

Image credit: Eva Rinaldi https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taylor_Swift_%286966830273%29.jpg

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 6, 2023 | Contracts, General

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Arthur C. Clarke

Do you recall when Netscape Navigator was released in December 1994? I suspect not. You may not have been born or you might have been too young to take notice. This software marked the public’s first widespread introduction to a user-friendly web browser, and it was a big deal at the time. I remember buying a copy on disk from Egghead Software in Boston and trying (with limited success) to access the World Wide Web using a dialup modem.

Of course, few people foresaw that Navigator would set off the “dotcom boom,” which ended with the “dotcom crash” in 2000, only to be followed by the ubiquitous internet technologies we live with today

Will OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT in November 2022 be remembered as a similar event for artificial intelligence? It may prove to be as significant as the invention of the printing press, as Henry Kissinger and his co-authors suggest. (link, WSJ paywall). Or, it may signal the demise of the human race, as Stephen Hawking warned. Or, once the novelty wears off it may simply become another forgotten episode in the decades-long AI over-hype cycle

However, for now one thing is clear: there will be a lot of lawyering to be done.

When the internet took off in the late ‘90s a vast number of legal issues emerged, keeping lawyers busy for years afterwards. However, it wasn’t immediately obvious that this would occur, and issues emerged slowly over time. By comparison, in 2023 generative AI – as represented by ChatGPT and other “large language models” (LLMs) – has landed like a bomb. Seemingly hundreds of new products are being released daily. Countless new companies are being formed to join the “AI gold rush” of 2023.

So, what are the legal issues (so far)? Warning, this topic is already vast, so what follows is a selective summary. I hope to write about these issues in more detail in the future.

AI and Copyright Law

At least for the moment, when it comes to generative AI, copyright law is the primary battlefield. The copyright issues can be divided into legal questions that deal with the “output” side versus the “input” or “training” side.

The Output Issue – Who Owns An AI Model’s Output? Who owns the copyright in works created by AI image generators, whether autonomously created or a human-AI blend?

I covered this topic from the perspective of the Copyright Office in a recent post. Generative AI Images Struggle for Copyright Protection. Shortly after I published that post the Copyright Office issued a policy statement, Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence, reaffirming its policy that works be the product of human authorship, but noting that there is a substantial grey area that will need to be decided on a case-by-case basis:

[works] containing AI-generated material [may] also contain sufficient human authorship to support a copyright claim. For example, a human may select or arrange AI-generated material in a sufficiently creative way that “the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship.” Or an artist may modify material originally generated by AI technology to such a degree that the modifications meet the standard for copyright protection. In these cases, copyright will only protect the human-authored aspects of the work, which are “independent of ” and do “not affect” the copyright status of the AI-generated material itself.

The Copyright Office has also created a web page tracking its activities in copyright AI, including an initiative to examine the copyright law and policy issues raised by AI technology. (link)

9th Cir.: Monkey selfie not copyright-protected

However, the Copyright Office is not the last word when it comes to AI and copyrightability – the federal courts are, and the issue is pending in a lawsuit before the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia (Thaler v. Perlmutter). Suffice it to say that there are no court decisions as yet, and all monkey-business aside who (if anyone) owns AI outputs scraped from the internet is an open (and rapidly evolving) question.

The Input Issue – Can You Use Copyrighted Content To Train An AI LLM? The training stage of AI tools requires the scraping and extraction of relevant information from underlying datasets (typically the internet), which contain copyright protected works. Can AI companies simply hoover up copyright-protected works without the consent of their owners and use that material to “train” LLMs?

AI companies think so, but content creators think otherwise. Getty has filed suit against Stability AI in the U.S. (link) and in a parallel case in London, claiming that this company illegally copied over 12 million photographs from Getty’s website to train Stable Diffusion. Other cases have been filed on the same issue (Andersen v. Stability AI, pending N.D. Cal.). The central legal issue in these cases is whether unauthorized use of copyrighted materials for training purposes is illegal or (as the AI companies are certain to assert) “transformative” and therefore protected under the fair use doctrine? The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Warhol v. Goldsmith is likely to have some bearing on this issue. (sarcasm ….)

While the legal question under U.S. law may be whether these activities qualify as fair use, in the EU the copyright aspects of training are likely to fall under the text and data mining (TDM) exceptions in the Copyright in Digital Single Market (CDSM) Directive. (To go in depth on the TDM exceptions see Quintais, Generative AI, Copyright and the AI Act).

However, the issues surrounding output ownership and the utilization of copyrighted materials to train LLMs are merely scratching the surface. It’s easy to foresee that copyright law and AI are going to intersect in other ways. An example of this is cases involving music that copies an artist’s “artistic style” or “voice”. At present copyright law does not protect artistic style. But for the first time, music AI systems make it easy to copy a style or an artist’s voice, so there will be pressure on the law to address this form of copying. It remains to be seen whether copyright law will expand to encompass artistic style, or whether artists will have to rely on doctrines such as the right of publicity or “passing off.”

Liability Shield Under CDA/Section 230

While the copyright issues in AI are complex, the legal issues around AI are not limited to copyright. An AI could generate defamatory content.

Even worse, it could be used to create harmful or dangerously wrong information. If a user prompts an AI for cocktail instructions and it offers a poisonous concoction, is the AI operator liable? What if the AI instructs someone on how to build a dangerous weapon, or to commit suicide? What if an AI “hallucination” (aka false information generated by an AI) causes harm or injuries?

Controversy over online companies’ liability for harmful content has led to countless litigations, and generative artificial intelligence tools are likely to be pulled into the fray. If ChatGPT and other LLMs are deemed to be “information content providers” they will not be immunized by Section 230, as it exists today.

Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch alluded to this during oral argument in Gonzalez v. Google, where he suggested that generative AI would not be covered by Section 230’s liability shield. (link, p. 49) Two of Section 230’s 1996 congressional co-authors have publicly stated that it does not – “If you are partly complicit in content creation, you don’t get the shield.” (link)

Section 230 was enacted to protect websites from liability based on user inputs. However, given the unpopularity of Section 230 on both sides of the isle it seems unlikely that Congress will amend Section 230, or pass new laws, to limit the liability of AI companies whose products generate illegal content based on user inputs. The opposing view, as observed by internet law scholar Prof. Eric Goldman, is that “we need some kind of immunity for people who make [AI] tools . . . without it, we’re never going to see the full potential of A.I.” (link, behind NYT paywall).

Contracts and Open Source

Because copyright-protected works can also be the subject of contracts, there will be issues of contract law that intersect with copyright. We can already see examples of this. For example, In the Getty/Stability AI case mentioned above, Getty’s website terms prohibit the very use Stability AI made of Getty photos. A class action suit has been filed over AI scraping of code on Github without providing attribution required by the applicable OSS license agreements, raising questions about the risks of using AI in software development. That suit also relies on DMCA Section 1202 for removing copyright management information (CMI).

These cases point to the fact that companies need to monitor and regulate their use of AI code generators to avoid tainting their code bases. Transactional lawyers (licensing, M&A) will have to be alert to these issues. Suffice it to say that there are significant questions over whether using open source code requires compliance with restrictions of the open source licenses.

Patent Law

What if an AI creates a patentable invention? Similar to copyright, the USPTO will only consider inventions from “natural persons” and not machines. This has already been the subject of litigation (Thaler v. Vidal, CAFC 2022; yes, the same Thaler that’s the plaintiff in the copyright case cited above) and an unsuccessful Supreme Court appeal (cert. denied). The USPTO is conducting hearings concerning AI technologies and inventorship issues, however at present the law, as stated by the CAFC in Thaler, is that “only a natural person can be an inventor, so AI cannot be.” For the foreseeable future there will be significant questions about the ability to patent inventions that were conceived with the assistance of AI.

Government Regulation

Governments worldwide are waking up to the issues created by AI. The U.S. has issued policy statements and executive orders. The U.S. Senate is holding hearings into an AI regulatory framework. While there is no comprehensive U.S. federal regulatory scheme in place regarding AI technologies today, it may be just a matter or time. When AI scientists warn that the risk of extinction from AI is comparable to pandemics and nuclear war, Congress is likely to pay attention.

Governments worldwide are waking up to the issues created by AI. The U.S. has issued policy statements and executive orders. The U.S. Senate is holding hearings into an AI regulatory framework. While there is no comprehensive U.S. federal regulatory scheme in place regarding AI technologies today, it may be just a matter or time. When AI scientists warn that the risk of extinction from AI is comparable to pandemics and nuclear war, Congress is likely to pay attention.

Pending federal umbrella legislation, individual agencies are not sitting on their hands. Every day seems to bring some new agency action. The FDA has weighed in on the regulation of machine learning-enabled medical devices. The SEC and CFTC have already weighed in, focusing on credit approval and lending decisions. The FTC is pondering how to use its authority to promote fair competition and guard against unfair or deceptive AI practices. Although not a government agency, in early January NIST, at the direction of Congress, published a voluntary AI Risk Management Framework that is likely to be one of the first of many industry standards. The CFTC, DOJ, EEOC, FTC have issued a joint statement expressing their concerns about potential bias in AI systems. (link) Homeland Security has announced formation of a task force to study the role of AI in international trade, drug smuggling, online child abuse and secure infrastructure.

Not wanting to be left behind, California, Connecticut, Illinois and Texas are starting to take action to protect the public from what they perceive to be the potential harms of AI technology. (For a deeper dive see How California and other states are tackling AI legislation)

However, it would be a mistake to focus solely on U.S. law. International law – and in particular the EU – will play a significant role in the evolution of AI. The EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act (a work in progress) is far ahead of the U.S. in creating a legal framework to regulate AI. While the AI Act would regulate the use of AI technologies only in Europe, it could set a global standard, much like the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) has done for privacy regulation. (To go in depth on this topic see Perkins Coie, The Latest on the EU’s Proposed Artificial Intelligence Act).

The Future of AI and Law

I expect that the topics I’ve touched on above will prove to be only the tip of the AI iceberg. Regulators are already looking at issues involving privacy, facial recognition, deep fakes and disinformation, substantive criminal law (criminal behavior by an AI), anti-discrimination law and racial or gender bias.

Just as it was nearly impossible to foresee the massive volume of litigation that would follow the growth of the internet following passage of the DMCA in 1998 and Section 230 of the CDA in 1996, the legal issues around AI are only beginning to be understood.

I’ve said it many times before on this blog, but I’ll say it again – stay tuned. And lawyers – Get ready!

******************

Update, June 26, 2023: it didn’t take long for the first defamation suit to be filed. See Australian mayor readies world’s first defamation lawsuit over ChatGPT content.

by Lee Gesmer | Apr 21, 2023 | Copyright

Software copyright is an important area of copyright law. However, it has proven devilishly difficult for the courts to apply. As the Second Circuit observed 30 years ago, trying to apply copyright law to software is often an “attempt to fit the proverbial square peg in a round hole.” Judges know this – I’ll never forget the time that Massachusetts Federal District Court Judge Rya Zobel, during an initial case conference in a copyright case, looked me in the eye and said, “we aren’t going to have to compare source codes in this case, are we Mr. Gesmer?” (We didn’t, the case settled soon afterwards).

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the CAFC) has grappled with this challenge, most notably in its two controversial decisions in Oracle v. Google. (2014, 2018).

Now the CAFC has issued an important decision in SAS Institute, Inc. v. World Programming Limited (April 6, 2023; Newman dissenting). The issue in this case is one that I encountered in a copyright suit in Boston, so it’s of particular interest to me. More on that below.

SAS Institute and World Programming

SAS Institute is a successful software company. Its annual revenues exceed $3 billion, and it has more than 12,000 employees. Its statistical analysis software — the “SAS System” – is used in 3,000+ companies worldwide.

Success attracts imitation, and World Programming (now part of Altair) developed a “clone” of the SAS Software. SAS didn’t react kindly to the competition – it has conducted a more-than 10 year, multi-nation legal challenge, suing World Programming once in England and twice in the United States.

What makes SAS’s most recent copyright case against World Programming unusual is the subject matter. Most software copyright litigation involves the “literal elements” of computer programs – the “source” and “object” code – essentially the “written words” or the machine code (ones and zeros) of the software.

“Non-literal” Copyright Infringement

SAS v. World Programming, however, involved the “non-literal” elements of SAS’s system. The courts define “non-literal elements” as the structure, sequence, and organization and the user interface of software. Basically, anything other than the computer code. SAS alleged that World Programming illegally copied input syntax formats and output design styles – non-literal components of the SAS System.

The idea that non-literal components of a software program can be protected by copyright has been acknowledged since the 1980s. For the last 30 years most courts have followed the “abstraction-filtration-comparison” test (AFC test) established in the 1992 Second Circuit decision in Altai v. Computer Associates. The AFC test requires the court to (1) break a software program into its constituent parts (abstraction), (2) filter out unprotectable elements (filtration) and (3) compare the remaining protectable elements to the allegedly infringing work (comparison).

If this sounds challenging to you, you are right. However, relatively few cases have actually had to undertake the real-world application of this test to the non-literal elements of a software program. And, where they have the plaintiff has almost always lost.

The District Court Case

SAS filed this case in the Eastern District of Texas. The district court judge proceeded to apply the Altai AFC test by conducting a hearing to “filter out” unprotectable elements of the SAS software. Examples of unprotected elements include ideas, facts, information in the public domain, merger material, scènes à faire and conventional display elements. Case law has established that abstraction and filtration (steps 1 and 2 of the AFC test) is performed by the judge, not the jury.

The district court held what it termed a “copyrightability hearing” and implemented an alternating, burden-shifting framework in which SAS was required to prove a valid copyright and “factual copying.” The burden then shifted to defendant (World Programming) to prove that some or all of the copied material is unprotectable. The burden then shifted back to SAS to respond and persuade the court otherwise.

Think of this as a tennis volley in which the ball crosses the net three times.

SAS satisfied the first part of this test – it showed that it had a registered copyright, and that World Programming had copied some elements of the SAS System. However, World Programming responded with evidence that many of the non-literal components of the SAS System contained factual elements, elements that were not original to SAS or that were in the public domain, unprotected mathematical and method components, conventional display elements and merger elements. World Programming asserted that all of these components should be filtered out and excluded from step 3 of the AFC test – comparison of the two software programs.

At that point, under the judge’s burden shifting approach, the burden fell on SAS to respond and address these defenses.

Inexplicably, SAS failed to do this. The court stated –

SAS has not attempted to show what World Programming pointed to as unprotectable is indeed entitled to protection. . . . Instead, when the burden shifted back to SAS, it was clear SAS had done no filtration; they simply repeated and repeated that the SAS System was “creative.” . . . SAS’s failures have raised the untenable specter of the Court taking copyright claims to trial without any filtered showing of protectable material within the asserted work. This is not a result that this Court can condone. These failures rest solely on SAS and the consequences of those failures necessarily rest upon SAS as well.

The district court then dismissed the case. SAS appealed to the Federal Circuit – a court that is notoriously pro-copyright. (See the two Oracle decisions linked to above). SAS likely planned for any appeal to go to the Federal Circuit by asserting patent infringement against World Programming and later dropping its patent claims. Nevertheless, that was enough to give the Federal Circuit jurisdiction over any appeal.

Appeal to the Federal Circuit

On appeal the central question was procedural: Was it SAS’s burden to prove that the copied elements were protectable, or was it World Programming’s burden to prove that they were not? In other words, the issue was who bears the burden of proving, as part of the filtration analysis, that the elements the defendant copied are unprotectable – the plaintiff (copyright owner) or the defendant (alleged infringer)?

The Federal Circuit was not impressed with SAS’s arguments on appeal. It noted that rather than participate in the steps required by the Altai AFC test, SAS “failed or refused” to identify the constituent elements of the SAS software that it claimed were protectable. Instead, it argued that its software was “creative” and that it had provided evidence that World Programming had engaged in “factual copying.” But it provided no evidence in relation to the “filtration” step under the 3-part Altai AFC test.

The Federal Circuit found the trial court judge’s procedure to be appropriate: “a court may reasonably adopt an analysis to determine what the ‘core of protectable expression’ is to provide the jury with accurate elements to compare in its role of determining whether infringement has occurred.” The court concluded that SAS failed to “articulate a legally viable theory” and affirmed dismissal.

In other words, to continue the tennis analogy, SAS served the ball (showed that it had copyright registrations and that World Programming had copied some elements). World Programming returned the ball, introducing evidence that many of the elements SAS had identified were unprotected by copyright, and needed to be “filtered out” before the SAS and World Programming software programs were compared. However, SAS was unable to return that volley – “The district court found that SAS refused to engage in the filtration step and chose instead to simply argue that the SAS System was ‘creative.’”

20-20 Design v. Real View – Same Issue, No Controversy

While this is an important software copyright case and will be used defensively by copyright defendants in the future, it caught my attention for a second reason, which is that I dealt with the same issue in 20-20 Design v. Real View LLC, a copyright infringement case I tried to a jury in Boston in 2010. That case dealt with the graphical user interface of a software program – “nonliteral” elements of the software. Like World Programming in the SAS case, Real View allegedly created a “clone” program, but the cloning didn’t involve the source or object code, only parts of the graphical user interface.

Massachusetts Federal District Court Judge Patti Saris ordered 20-20 Design, the plaintiff/copyright owner, to identify the elements of its software that it claimed had been infringed. Unlike SAS, 20-20 Design complied. It provided a list of 60 elements, and the court held what Judge Saris called (by analogy) a “Markman”-style evidentiary hearing, which included evidence and testimony from experts on both sides. In effect, this was the “copyrightability hearing” held by the court in the SAS case.

Judge Saris then issued a copyrightability decision holding that almost all of the items were not individually protectible. They could, however, be protected as a “compilation.” However, she ruled that as a “compilation,” the plaintiff-copyright owner was required to prove that the defendant’s software interface was “virtually identical” – a much more difficult standard to meet than the “substantial similarity” standard applied in most copyright litigation.

(Humble brag: 20-20 Design was seeking damages of $2.8 million. However, the “virtually identical” standard proved to be its downfall. Without going into detail, suffice it to say that after a 10-day jury trial and post-trial motions the judge entered judgment for 20-20 Design against Real View (my client) in the amount of $4,200. (link)

When I read the decision in SAS v. World Programming I immediately related it to the 20-20 Design/Real View case, but I couldn’t recall how Judge Saris had allocated the burden-of-proof. When I refreshed my memory I realized why – the judge and the parties never discussed this issue. It seems that everyone assumed that the plaintiff-copyright holder (20-20 Design) had the burden of proof. After 20-20 identified the copied elements Real View argued that most of them should be filtered out and 20-20 Design (unlike SAS) responded with counter arguments. In other words, the ball went over the net three times, and the judge was able to apply the Altai AFC test and “filter” 20-20’s software before trial.

Thinking back on how smoothly this procedure went in my case, it’s difficult for me to imagine how SAS chose the strategy that cost it the World Programming case, unless this case was just an attempt to outspend a smaller competitor and drive it out of the market with litigation expenses. SAS is a multi-billion-dollar company. Its lawyers are highly experienced. Why SAS chose a case strategy that seemed doomed to failure is a bit of a mystery. One possibility is that SAS knew that if it identified the elements it would be forced into a copyright compilation theory that requires proof that the infringing work is “virtually identical” to plaintiff’s work, a burden that SAS believed it could not satisfy. Another is that it gambled that the Federal Circuit – which is notoriously protective of copyright owners – would see the law its way and reverse the district court. We will never know.

Although it remains a mystery why SAS chose a case strategy that seemed destined to fail, the SAS v. World Programming decision has important implications for software copyright law. It clarifies the burden-shifting process and emphasizes the importance that the plaintiff be fully prepared to engage in the Altai AFC test’s filtration step.

Will SAS appeal this decision to the Supreme Court? Given the resources that SAS has dedicated to its litigation with World Programming over the last decade it seems likely that it will. While I view it as doubtful that the Supreme Court will hear this case, you never know.

SAS Institute v. World Programming (Fed. Cir. April 6, 2023)