by Lee Gesmer | Jul 1, 2024 | Copyright

“AI models are what’s known in computer science as black boxes: You can see what goes in and what comes out; what happens in between is a mystery.”

Trust but Verify: Peeking Inside the “Black Box” of Machine Learning

In December 2023, The New York Times filed a landmark lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft, alleging copyright infringement. This case, along with a number of similar cases filed against AI companies, brings to the forefront a fundamental challenge in applying traditional copyright law to a revolutionary technology: Large Language Models (LLMs). Perhaps more than any copyright case that precedes them, these cases grapple with a form of alleged infringement that defies conventional legal analysis.

This article is the first in a three-part series that will examine the copyright implications of the AI development process.

Disclaimer: I’m not a computer or AI scientist. However, neither are the judges and juries that will be asked to apply copyright law to this technology, or the legislators that may enact laws regulating it. It’s unlikely that they will go much beyond the level of detail I’ve used here.

What are Large Language Models (LLMs)?

Large Language Models, or LLMs, are gargantuan AI systems that use a vast corpus of training data and billions to trillions of parameters. They are designed to understand, generate, and manipulate human language. They learn patterns from the data, allowing them to perform a wide range of language tasks with remarkable fluency. Their inner workings are fundamentally different from any previous technology that has been the subject of copyright litigation, including traditional computer software.

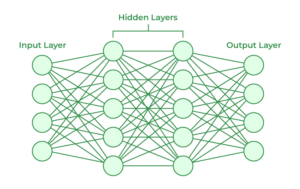

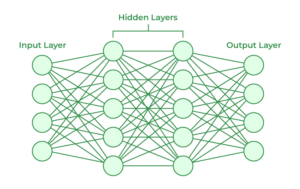

LLMs typically use transformer-based neural networks: interconnected nodes organized into layers that can perform computations. The strengths of these connections—the influences that nodes have on another—are what is learned during training. These are called the model parameters or weights, and they are represented as numbers.

Here’s a simplified explanation of what happens when you use an AI like a large language model:

- You input a prompt (your question or request).

- The computer breaks down your prompt into smaller pieces called tokens. These can be words, parts of words, or even individual characters.

- The AI processes these tokens through its neural network – imagine this like a complex web of connections. Each part of this network analyzes the tokens and figures out how they relate to each other.

- As it processes, the AI predicts the probability distribution for the next token based on what it learned during its training.

- The LLM selects tokens based on these probabilities and combines them to create a coherent response or output for you, the user.

The “large” in Large Language Models primarily refers to the enormous number of parameters these models contain – sometimes in the trillions. These parameters represent the model’s learned patterns and relationships, fine-tuned through exposure to massive amounts of text data. While larger and more diverse high-quality datasets can lead to better AI models, other factors such as model architecture, training techniques, and fine-tuning also play important roles in model performance.

How Do AI Companies Obtain Their Training Data?

AI companies employ various methods to acquire this data –

– Web scraping and crawling. One of the primary methods of data acquisition is web scraping – the automated process of extracting data from websites. AI companies deploy sophisticated crawlers that systematically browse the internet, copying text from millions of web pages. This method allows for the collection of diverse, up-to-date information but raises questions about the use of copyrighted material without explicit permission.

– Partnerships and licensing agreements. Some companies enter into partnerships or licensing agreements to access high-quality, curated datasets. For instance, OpenAI has partnered with organizations like the Associated Press to use its news archives for training purposes.

– Public datasets and academic corpuses. Many LLMs are trained, at least in part, on publicly available datasets and academic text collections. These might include Project Gutenberg’s collection of public domain books, scientific paper repositories, or curated datasets like the Common Crawl corpus.

– User-generated content. Platforms that interact directly with users, such as ChatGPT, can potentially use the conversations and inputs from users to further train and refine their models. This practice raises privacy concerns and questions about the ownership of user-contributed data.

In the context of the New York Times lawsuit, it’s worth noting that OpenAI, like many AI companies, has not publicly disclosed the full extent of its training data sources. However, it’s widely believed that the company uses a combination of publicly available web content, licensed datasets, and partnerships to build its training corpus. The lawsuit alleges that this corpus includes copyrighted New York Times articles, obtained without permission or compensation.

The Training Process: How Machines “Learn” From Data

Once acquired, the raw data undergoes several processing steps before it can be used to train an LLM –

– Data preprocessing and cleaning. The first step involves cleaning the raw data. This includes removing irrelevant information, correcting errors, and standardizing the format. This may involve stripping away HTML tags, removing advertisements, or filtering out low-quality content.

– Tokenization and encoding. Next, the text is broken down into smaller units called tokens. These might be words, parts of words, or even individual characters. Each token is then converted into a numerical representation that the AI can process. This step is crucial as it determines how the model will interpret and generate language.

During training, the LLM is exposed to this preprocessed data, learning to predict patterns and relationships between tokens. This is an iterative process where the model makes predictions, compares them to the actual data, and adjusts its internal parameters to improve accuracy. This process, known as “backpropagation,” is repeated billions of times across the entire dataset. In a large LLM this can take months, operating 24/7 on a massive system of graphics processing chips.

The Transformation From Text to Numbers

For purposes of copyright law, here’s the crux of the matter: the AI industry asserts that after this process, the original text no longer exists in any recognizable form within the LLM. The model becomes a vast sea of numbers, with no direct correspondence to the original text. If true, this transformation creates a fundamental challenge for copyright law –

– No Side-by-Side Comparison: In traditional copyright cases, courts rely heavily on comparing the original work side-by-side with the allegedly infringing material. With LLMs, this is impossible. You can’t “read” an LLM or print it out for comparison.

– Black Box Nature: The internal workings of LLMs are often referred to as a “black box.” Even the developers may not fully understand how the model arrives at its outputs.

– Dynamic Generation: The AI industry claims that LLMs don’t store and retrieve text in a conventional database format; they generate it dynamically based on learned patterns. This means that any similarity to copyrighted material in the output is a result of statistical prediction, not direct copying.

– Distributed Information: The AI industry claims that Information from any single source is distributed across countless parameters in the model, making it impossible to isolate the influence of any particular work.

However, copyright owners do not concede that completed AI models (as distinct from the training data) are only abstracted statistical patterns of the training data. Rightsholders assert that LLMs do indeed retain the expressions of the original works on which they have been trained. There are studies showing the LLM models are able to regurgitate their training materials, and the New York Times lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft shows 100 examples of this. See also Concord Music Group v. Anthropic (alleging that song lyrics can be accessed verbatim or near-verbatim from Claude). Rightsholders argue that this could only occur if the models encode the expressive content of these works.

Copyright Implications

Assuming the AI developers’ explanation to be correct (if its not the infringement case against them is strong), AI technology creates unprecedented challenges for copyright law –

– Proving Infringement: How can a plaintiff prove infringement when the allegedly infringing material can’t be directly observed or compared?

– Fair Use Analysis: Traditional fair use factors, such as the amount and substantiality of the portion used, become difficult to apply when the “portion used” is transformed beyond recognition.

– Substantial Similarity: The legal test of “substantial similarity” between works becomes almost meaningless in the context of LLMs.

– Expert Testimony: Courts will likely have to rely heavily on expert testimony to understand the technology, but even experts may struggle to definitively prove or disprove infringement.

For all of these reasons, to prove copyright infringement plaintiffs such as the New York Times may be limited to claiming copyright infringement based on the “intermediate” copies that are used in the training process and user-prompted output, rather than the LLM models themselves.

Conclusion

The NYT v. OpenAI case and others raising the same issue highlight a fundamental mismatch between traditional copyright law and the reality of LLM technology and the AI industries’ fair use defense. The outcome of this case could reshape our understanding of copyright in the digital age, potentially requiring new legal tests and standards that can account for the invisible, transformed nature of information within AI systems.

Part 2 in this series will focus on the legal issues around the “input problem” of using copyrighted material for training. Part 3 will look at the “output problem” of AI-generated content that may copy or resemble copyrighted works, including what the AI industry calls “memorization.” As we’ll see, each of these issues presents its own unique challenges in the context of a technology that defies traditional legal analysis.

Continue reading Part 2 and Part 3 of this series.

by Lee Gesmer | May 26, 2024 | Copyright

Copyright secondary liability can be difficult to wrap your head around. This judge-made copyright doctrine allows copyright owners to seek damages from organizations that do not themselves engage in copyright infringement, but rather facilitate the infringing behavior of others. Often the target of these cases are internet service providers, or “ISPs.”

Secondary liability has three separate prongs, “contributory” and “vicarious” infringement, and “inducement.” The third prong – inducement – is important but seen infrequently. For the elements of this doctrine see my article here.

Here’s how I outlined the elements of contributory and vicarious liability when I was teaching CopyrightX:

These copyright rules were the key issue in the Fourth Circuit’s recent blockbuster decision in Sony v. Cox Communications (4th Cir. Feb. 20, 2024).

In a highly anticipated ruling the court reversed a $1 billion jury verdict against Cox for vicarious liability but affirmed the finding of contributory infringement. The decision is a significant development in the evolving landscape of ISP liability for copyright infringement.

Case Background

Cox Communications is a large telecommunications conglomerate based in Atlanta. In addition to providing cable television and phone services it acts as an internet service provider – an “ISP” – to millions of subscribers.

The case began when Sony and a coalition of record labels and music publishers sued Cox, arguing that the ISP should be held secondarily liable for the infringing activities of its subscribers. The plaintiffs alleged that Cox users employed peer-to-peer file-sharing platforms to illegally download and share a vast trove of copyrighted music, and that Cox fell short in its efforts to control this rampant infringement.

A jury found Cox liable under both contributory and vicarious infringement theories, levying a jaw-dropping $1 billion in statutory damages – $99,830.29 for each of the 10,017 infringed works. Cox challenged the verdict on multiple fronts, contesting the sufficiency of the evidence and the reasonableness of the damages award.

The Fourth Circuit Opinion

On appeal, the Fourth Circuit dissected the two theories of secondary liability, arriving at divergent conclusions. The court sided with Cox on the issue of vicarious liability, finding that the plaintiffs failed to establish that Cox reaped a direct financial benefit from its subscribers’ infringing conduct. Central to this determination was Cox’s flat-fee pricing model, which remained constant irrespective of whether subscribers engaged in infringing or non-infringing activities. The mere fact that Cox opted not to terminate certain repeat infringers, ostensibly to maintain subscription revenue, was deemed insufficient to prove Cox directly profited from the infringement itself.

However, the court took a different stance on contributory infringement, upholding the jury’s finding that Cox materially contributed to known infringement on its network. The court was unconvinced by Cox’s assertions that general awareness of infringement was inadequate, or that a level of intent tantamount to aiding and abetting was necessary for liability to attach. Instead, the court articulated that supplying a service with the knowledge that the recipient is highly likely to exploit it for infringing purposes meets the threshold for contributory liability.

Given the lack of differentiation between the two liability theories in the jury’s damages award, coupled with the potential influence of the now-overturned vicarious liability finding on the damages calculation, the court vacated the entire award. The case now returns to the lower court for a new trial, solely to determine the appropriate measure of statutory damages for contributory infringement.

Relationship to the DMCA

This article’s header graphic illustrates the relationship between the secondary liability doctrines and the protection of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), Section 512(c) of the Copyright Act. As the graphic reflects, all three theories of secondary liability lie outside the DMCA’s safe harbor protection for third-party copyright infringement. The DMCA requires that a defendant satisfy multiple safe harbor conditions (See my 2017 article – Mavrix v. LiveJournal: The Incredible Shrinking DMC for more on this). If a plaintiff can establish the elements of any one of the three theories of secondary liability the defendant will violate one or more safe harbor conditions and lose DMCA protection.

Implications

The court’s decision signals a notable shift in the contours of vicarious liability for ISPs in the context of copyright infringement. By requiring a causal nexus between the defendant’s financial gain and the infringing acts themselves, the court has raised the bar for plaintiffs seeking to prevail on this theory.

The ruling underscores that simply profiting from a service that may be used for both infringing and non-infringing ends is insufficient; instead, plaintiffs must demonstrate a more direct and meaningful link between the ISP’s revenue and the specific acts of infringement. This might entail evidence of premium fees for access to infringing content or a discernible correlation between the volume of infringement and subscriber growth or retention.

While Cox may take solace in the reversal of the $1 billion vicarious liability verdict, the specter of substantial contributory infringement damages looms large as the case heads back for a retrial.

For ISPs, the ruling serves as a warning to reevaluate and fortify their repeat infringer policies, ensuring they go beyond cosmetic compliance with the DMCA’s safe harbor provisions. Proactive monitoring, prompt responsiveness to specific infringement notices, and decisive action against recalcitrant offenders will be key to mitigating liability risks.

On the other side of the equation, copyright holders may need to recalibrate their enforcement strategies, recognizing the heightened evidentiary burden for establishing vicarious liability. While the contributory infringement pathway remains viable, particularly against ISPs that display willful blindness or tacit encouragement of infringement, the Sony v. Cox decision underscores the importance of marshaling compelling evidence of direct financial benefit to support vicarious liability claims.

As this case enters its next phase, the copyright and technology communities will be focused on the outcome of the damages retrial. Regardless of the ultimate figure, the Fourth Circuit’s decision has already left a mark on the evolving landscape of online copyright enforcement.

Header image is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

by Lee Gesmer | May 17, 2024 | Copyright

Many aspects of copyright law are obscure and surprising, even to lawyers familiar with copyright’s peculiarities. An example of this is copyright law’s three-year statute of limitations.

The Copyright Act states that “no civil action shall be maintained under the provisions of this title unless it is commenced within three years after the claim accrued.” 17 U. S. C. §507(b). In the world of copyright practitioners this is understood to mean that so long as a copyright remains in effect and infringements continue, an owner’s rights are not barred by the statute of limitations. However, they may be limited to damages that accrued in the three years before the owner files suit. This is described variously as a “three-year look-back,” a “rolling limitations period” or the “separate-accrual rule.”

This is what allowed Randy Wolfe’s estate to sue Led Zeppelin in 2014 for an alleged infringement that began in 1971.

However, there is a nuance to this doctrine – what if the copyright owner isn’t aware of the infringement? Is the owner still limited to damages accrued in the three years before he files suit?

That is the scenario the Supreme Court addressed in Warner Chappell Music, Inc. v. Nealy (May 9, 2024).

Background Facts

Songwriter Sherman Nealy sued Warner Chappell in 2018 for infringing his music copyrights going back to 2008. Warner responded that under the “three year look-back” rule Nealy’s damages were limited to three years before he filed suit. Nealy argued that his damages period should extend back to 2008, since his claims were timely under the “discovery rule” – he was in prison during much of this period and only learned of the infringements in 2016.

Nealy lost on this issue in the district court, which limited his damages to the infringer’s profits during the 3 years before he filed suit. The 11th Circuit reversed, holding that Nealy could recover damages beyond 3 years if his claims were timely – meaning that the case was filed within three years of when Nealy discovered the infringement.

The Supreme Court Decision

The Supreme Court affirmed the 11th Circuit and resolved a circuit split, holding:

1 – The Copyright Act’s 3-year statute of limitations governs when a claim must be filed, not how far back damages can go.

2 – If a claim is timely, the plaintiff can recover damages for all infringements, even those occurring more than 3 years before suit. The Copyright Act places no separate time limit on damages.

However, lurking within this ruling is another copyright law doctrine that the Court did not address that could render its ruling in Nealy moot – that is the proper application of the “discovery rule” under the Copyright Act. Under the discovery rule a claim accrues when “the plaintiff discovers, or with due diligence should have discovered” the infringement. (Nealy, Slip Op. p. 2). Competing with this is the less liberal “occurrence” rule, which holds that, in the absence of fraud or concealment, the clock starts running when the infringement occurs. Under the discovery rule Nealy would be able to recover damages back to 2008. Under the occurrence rule his damages would be limited to the three years before he filed suit, since he does not allege fraud or concealment.

However, the question of which rule applies under the Copyright Act has never been addressed by the Supreme Court, and is itself the subject of a circuit split. The Court assumed, without deciding and solely for purposes of deciding the issue before it, that the discovery rule does apply to copyright claims. If the discovery rule applies Nealy has a claim to retroactive damages beyond three years. If it does not, Nealy’s damages would be limited to the three years before he filed suit.

Justice Gorsuch, joined by Justices Thomas and Alito, focused on this in his dissent, arguing the Court should not have decided the issue when the “discovery vs. occurrence” issue has not been addressed:

The Court discusses how a discovery rule of accrual should operate under the Copyright Act. But in doing so it sidesteps the logically antecedent question whether the Act has room for such a rule. Rather than address that question, the Court takes care to emphasize that its resolution must await a future case. The trouble is, the Act almost certainly does not tolerate a discovery rule. And that fact promises soon enough to make anything we might say today about the rule’s operational details a dead letter.

Clearly, in the view of at least three justices, if and when the discovery vs. occurrence rule issue comes before the Court it could decide against the discovery rule in copyright cases, rendering its decision on damages in the Nealy case, and cases like it, moot.

State of the Law Today

What does this all boil down to? Here are the rules as they exist today –

– A copyright owner has been aware of an infringing musical work for 20 years. She finally sues the infringer. Her damages are limited by the three year damages bar. They may be limited even further based on the laches doctrine.

– A copyright owner has been meditating alone in a cave in Tibet for 20 years. She’s had no access to information from the outside world. Upon her return she discovers that someone has been infringing her literary work for the last 20 years. Depending on whether the federal circuit applies the discovery or the occurrence rule, she may recover damages for the entire 20 period, or just the preceding three years. Her lawyers should do some careful forum shopping.

– A copyright owner discovers someone has secretly been infringing her copyright in computer source code for 20 years. The source code was non-public, and therefore the infringement was concealed. She may recover damages for the full 20 year period.

Implications

The decision is a win for copyright plaintiffs, allowing them to reach back and get damages beyond 3 years – assuming their claims are timely and they are in a circuit that apples the discovery rule. But the Court left the door open to decide the more important question of whether the discovery rule applies to the Copyright Act’s statute of limitations at all. If not, the window for both filing claims and recovering damages will shrink. When this issue will reach the Supreme Court is uncertain. However, the Court has the opportunity to take it up as soon as next term. See Hearst Newspapers, LLC v. Martinelli, No. 23-474 (U.S. petition for cert. filed Nov. 2, 2023). In the meantime, the outer boundary of damages is limited only by the discovery rule (if it apples), not any separate damages bar. Plaintiffs with older claims should take note, as should potential defendants doing due diligence on liability exposure.

Update: On May 20, 2024, the Supreme Court of the United States denied the petition for certiorari in Hearst Newspapers, L.L.C. v. Martinelli, thereby declining to decide whether the discovery rule applies to copyright infringement claims and leaving the rule intact.

Header image attribution: Resource by Nick Youngson CC BY-SA 3.0 Pix4free

by Lee Gesmer | Nov 27, 2023 | Copyright, General

If you follow developments in artificial intelligence, two recent items may have caught your attention. The first is a Copyright Office submission by the VC firm Andreessen Horowitz warning that billions of dollars in AI investments could be worth less if companies developing this technology are forced to pay for their use of copyrighted data. “The bottom line is this . . . imposing the cost of actual or potential copyright liability on the creators of AI models will either kill or significantly hamper their development.”

The second item is OpenAI’s announcement that it would roll out a “Copyright Shield,” a program that will provide legal defense and cost-reimbursement for its business customers who face copyright infringement claims. OpenAI is following the trend set by other AI providers, like Microsoft and Adobe, who are promising to indemnify their customers who may fear copyright lawsuits from their use of generative AI.

Underlying these two news stories is the fact that the explosion of generative AI has the copyright community transfixed and the AI industry apprehensive. The issue is this: Does copyright fair use allow AI providers to ingest copyright-protected works, without authorization or compensation, to develop large language models, the data sets that are at the heart of generative artificial intelligence? Multiple lawsuits have been filed by content owners raising exactly this issue.

The Technology

The current breed of generative AIs is powered by large language models (LLMs), also known as Foundation Models. Examples of these systems are ChatGPT, DALL·E-3, MidJourney and Stable Diffusion.

This technology requires that developers collect enormous databases known as “training sets.” This almost always requires copying millions of images, videos, audio and text-based works, many of which are protected by copyright law. When the data is scraped from the web this is potentially a massive infringement of copyright. The risk for AI companies is that, depending on the content (text, images, music, movies), this could violate the exclusive rights of reproduction, distribution, public performance, and the right to create derivative works.

of images, videos, audio and text-based works, many of which are protected by copyright law. When the data is scraped from the web this is potentially a massive infringement of copyright. The risk for AI companies is that, depending on the content (text, images, music, movies), this could violate the exclusive rights of reproduction, distribution, public performance, and the right to create derivative works.

However, for purposes of copyright fair use analysis it’s important to recognize that the downloads are only an intermediate step in creating an LLM. Greatly simplified, here’s how it works:

In the process of creating an LLM model words are broken down into tokens, numerical representations of the word. Each token is a unique numerical ID. The numerical IDs are then transformed into high-dimensional vectors. These vectors are learned during the model’s training and capture semantic meanings and relationships.

Through multiple layers of transformation and abstraction the LLM identifies patterns and correlations within the data. Cutting edge systems like GPT-4 have trillions of parameters. Importantly, these are not copies or replications of the copyright-protected input data. This process of transformation minimizes the risk that any output will be infringing. A judge or jury viewing the data in an LLM would see no similarity between the original copyrighted text and the LLM.

Is Generative AI “Transformative“?

Because the initial downloads in this process are copies, they are technically a copyright infringement – a “reproduction.” Therefore, it’s up to the AI companies to present a legal defense that justifies the copying, and the AI development community has made it clear that this defense is based on copyright fair use. At the heart of the AI industry’s fair use argument is the assertion that AI training models are “non-expressive uses.” Copyright protects expression. Non-expressive use is the use of copyrighted material in a way that does not involve the expression of the original material.

Because the initial downloads in this process are copies, they are technically a copyright infringement – a “reproduction.” Therefore, it’s up to the AI companies to present a legal defense that justifies the copying, and the AI development community has made it clear that this defense is based on copyright fair use. At the heart of the AI industry’s fair use argument is the assertion that AI training models are “non-expressive uses.” Copyright protects expression. Non-expressive use is the use of copyrighted material in a way that does not involve the expression of the original material.

For the reasons discussed above, the AI industry has a strong argument that a properly constructed LLM is a non-expressive use of the copied data.

However, depending on the specific technology this may be an oversimplification. Not all AI systems are the same. They may use different data sets. Some, but not all, are designed to minimize “memorization” which makes it easier for end users to retrieve blocks of text or infringing images. Some systems use output filters to prevent end users from utilizing the LLM to create infringing content.

For any given AI system the fair use defense turns on whether the LLM is trained and filtered in such a way that its outputs do not resemble protected inputs. If users can obtain the original content, the fair use defense is more difficult to sustain.

There is a widespread assumption in the AI industry that, assuming an AI is designed with adequate safety measures, using copyright-protected content to train LLMs is shielded by the fair use doctrine. After all, the reasoning goes, the Second Circuit allowed Google to create a searchable index of copyrighted books under fair use. (Google Books, Hathitrust). And the Supreme Court permitted Google to copy Oracle’s Java API computer code for a different use. (Oracle v. Google). AI companies also point to cases holding that search engines, intermediate copying for the purpose of reverse engineering and plagiarism-detection software are transformative and therefore allowed under fair use. (Perfect 10 v. Google; Sega Enterprises v. Accolade; A.V. et al. v. iParadigms)

In each of these cases the use was found to be “transformative.” So long as the act of copying did not communicate the original protected expression to end users it did not interfere with the original expression that copyright is designed to protect. The AI industry contends that LLM-based systems that are properly designed fall squarely under this line of cases.

How Does Generative AI Impact Content Owners?

In evaluating AI’s fair use defense the commercial impact on content owners is also important. This is particularly true under the Supreme Court’s decision earlier this year in Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith. In Warhol the Court taught that, in a case that involved commercial copying of photographs, the fact that the copies were used in competition with the originals weighed against fair use.

AI developers will argue that, so long as users can’t use their generative AI systems to access protected works, there is no commercial impact on content owners. In other words, like in Google Books, the AI does not substitute for or compete with content owners’ original protected expression. No one can use a properly constructed AI to read a James Patterson novel or listen to a Joni Mitchell song.

The AIs should be able to distinguish Warhol by pointing out that they are not selling the actual copyrighted books or images in their data sets, and therefore – like in Google Books – they are causing the content owners no commercial harm. In other words, the AI developers will argue that the “intermediate copying” involved in creating and training an LLM is transformative where the resulting model does not substitute for any author’s original expression and the model targets a different economic market.

Does the authority of Google Books and the other intermediate copying cases extend to the type of machine learning that underpins generative AI? While the law regulating AI is in its infancy, several recent district court cases have given plaintiffs an unfriendly reception. In Thomson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence the defendant used West’s head notes and key number system to train a specialized natural language AI for lawyers. West claimed infringement. A Delaware federal district court judge denied Ross’s motion for summary judgment based on fair use, and held that the case must be decided by a jury. However, relying on the intermediate copying cases, the judge noted that Ross would have engaged in transformative fair use if its AI merely studied language patterns in the Westlaw headnotes and did not replicate the headnotes themselves. Since this is in fact how LLMs are trained on data, Ross’s fair use defense likely will succeed.

generative AI? While the law regulating AI is in its infancy, several recent district court cases have given plaintiffs an unfriendly reception. In Thomson Reuters v. Ross Intelligence the defendant used West’s head notes and key number system to train a specialized natural language AI for lawyers. West claimed infringement. A Delaware federal district court judge denied Ross’s motion for summary judgment based on fair use, and held that the case must be decided by a jury. However, relying on the intermediate copying cases, the judge noted that Ross would have engaged in transformative fair use if its AI merely studied language patterns in the Westlaw headnotes and did not replicate the headnotes themselves. Since this is in fact how LLMs are trained on data, Ross’s fair use defense likely will succeed.

In a second case, Kadrey v. Meta, the plaintiffs, book authors, claimed that Meta’s inclusion of their books in its AI training data violated their exclusive ownership rights in derivative works. The Northern District of California federal judge dismissed this claim. The judge noted that the LLM models could not be viewed as recasting or adapting the plaintiff’s books. And, the plaintiffs had failed to allege that the content of any output was infringing. “The plaintiffs need to allege and ultimately to prove that the AI’s outputs incorporate in some form a portion of the plaintiffs’ books.” Another N.D. Cal. case, Andersen v. Stability AI is consistent with these rulings.

While these cases are early in the evolution of the law of artificial intelligence they suggest how AI developers can take precautions to insulate themselves from copyright liability. And, as discussed below, the industry is already taking steps in this direction.

The Industry Is Adapting To The Copyright Threat

In the face of legal uncertainty, the AI industry is adapting to legal risks. The potential damages for copyright infringement are massive, and the unofficial Silicon Valley motto – “move fast and break things” – doesn’t apply with the stakes this high.

ChatGPT4: Create an image showing Jack Nicholson in The Shining

Early in the current generative AI boom (only a year ago) it was possible to use some of these systems to generate copyright- protected content. However, the dominant AI companies seem to have plugged this hole. Today, if I ask OpenAI’s ChatGPT to provide the lyrics to “All Too Well” by Taylor Swift it declines to do so. When I ask for the text of the opening paragraph of Stephen King’s “The Shining,” again it refuses and tells me that it’s protected by copyright. When I ask OpenAI’s text-to-image creator Dall·E for an image of Batman, Dall·E refuses, and warns me that what it will create will be sufficiently different from the comic book character to avoid copyright infringement.

These technical filters are illustrative of the ways that the industry can address the copyright challenge, short of years of litigation in the federal courts.

The first, and most obvious, is to train the systems not to provide infringing output. As noted, Open AI is doing exactly this. The Shining may have been downloaded and used to create and train Chat GPT, but it won’t let me retrieve the text of even a small part of that novel.

ChatGPT4: Create an image of Taylor Swift performing her song “All Too Well”

Another technical measure is minimization of duplicates of the same work. Studies have found that the more duplicates that are downloaded and processed in an LLM the easier it is for end-users to retrieve verbatim protected content. “Deduplication” is a solution to this problem.

Another option is to license copyrighted content and pay its creators. While this would be logistically challenging, a challenge of similar complexity has been met in the music industry, which has complex licensing rules that address different types of music licensing and a centralized database system to make that process accessible. If the courts prove to be hostile to AI’s fair use defense the generative AI field could evolve into a licensing regime similar to that of music.

Another solution is for the industry to create “clean” databases, where there is no risk of copyright infringement. The material in the database will have been properly licensed or will be comprised of public domain materials. An example would be an LLM trained on Project Gutenberg, Wikipedia and government websites and documents.

Given the speed at which AI is advancing I expect a variety of yet-to-be conceived or discovered infringement mitigation strategies to evolve, perhaps even invented by artificial intelligence.

International Issues

Copyright laws vary significantly across countries. It’s worth noting that there has been more legislative activity on the topics discussed in this post in the EU than the US. That said, as of the date of this post near the close of 2023 there is no consensus on how LLMs should be treated under EU copyright law.

post in the EU than the US. That said, as of the date of this post near the close of 2023 there is no consensus on how LLMs should be treated under EU copyright law.

Under a recent proposal made in connection with the proposed EU “AI Act,” providers of LLMs would need to “prepare and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary of the content used to train the model or system and information on the provider’s internal policy for managing copyright-related aspects.”

Additionally, they would need to demonstrate “that adequate measures have been taken to ensure the training of the model or system is carried out in compliance with Union law on copyright and related rights . . .”

The second of these two provisions would allow rights holders to opt out of allowing their works to be used for LLM training.

In contrast, the recent US AI Executive Order orders the Copyright Office to conduct a study that would include “the treatment of copyrighted works in AI training,” but does not propose any changes to US copyright law or regulations. However, US AI companies will have to pay close attention to laws enacted in the EU (or elsewhere), since – as has been the case with the EU’s privacy laws (GDPR) – they have the potential to become a de facto minimal standard for legal compliance worldwide.

Andreessen Horowitz and the Copyright Shield

What about the two news items that I mentioned at the beginning of this post? With respect to the Andreessen Horowitz warning of the cost of copyright risk on AI developers, in my view the risk is overstated. If AI developers design their systems with the proper precautions, it seems likely that the courts will find them to qualify for fair use.

As to OpenAI’s promise to indemnify end users, the risk to OpenAI is slim, since its output is rarely similar to inputs in its training data and its filters are designed to frustrate users who try to output copyrighted content. In any event end users are rarely the targets of infringement suits, as seen in the many copyright suits that have been filed to date, which all target only AI companies as defendants.

The Future

The application of US copyright law to LLM-based AI systems is a complex topic. I expect more lawsuits to be filed as what appears to be a massive revolution in artificial intelligence continues at breakneck speed. While traditional copyright law seems to favor a fair use defense, the devil is in the details of these complex systems, and the legal outcome is by no means certain.

***

Selected pending cases:

Andersen v. Stability AI, N.D. Cal.

J.L. v. Alphabet Inc., N.D. Cal.

P.M. v. OpenAI, N. Dist. Cal.

Doe v. GitHub, N.D. Cal

Thomson Reuters Enter. Ctr. GmbH v. Ross Intel. Inc., D. Del.

Kadrey v. Meta, N.D. Cal.

Sancton v. OpenAI, S.D. N.Y.

Doe v. GitHub, N.D. Cal.

by Lee Gesmer | Oct 26, 2023 | Copyright, General

By Lee Gesmer and Andrew Updegrove

Every citizen is presumed to know the law … and it needs no argument to show… that all should have free access to its contents.

U.S. Supreme Court in Georgia v. Public.Resource.Org (2020)

Many private organizations promulgate best-practice standards. Two examples you might be familiar with are the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM).

In the U.S., unlike most foreign countries, standards are developed “from the bottom up” by the private sector, rather than “from the top down” by government agencies or quasi-public bodies. In keeping with this division of labor, government agencies have come to rely extensively on private sector standards developers to provide standards suitable for adoption as regulations.

Federal law permits federal agencies to incorporate privately developed standards into law by referencing them in the Federal Register without reproducing them there. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) has more than 27,000 incorporated standards. States and municipalities do this as well, adding to that number. Once adopted the standards carry the force of law.

These private-government relationships are crucially important – they leverage specialized knowledge and industry expertise to formulate robust and reliable standards that the government could not create by itself, and save untold millions of tax dollars in avoided costs for government agencies that would otherwise have to generate them. The standards organizations that provide standards referenced into law, in turn, gain legal legitimacy and wider application for their standards.

There is also a commercial side to these relationships – many standards organizations support themselves in part by the sale of their standards.

Public.Resource.Org (Public Resource) is a nonprofit group that disseminates legal materials. Its website has posted thousands of standards, including those produced and copyrighted by ASTM. ASTM (along with two other standards organizations) sued Public Resource for copyright infringement. The case has been working its way through the courts for a decade. Absent a successful appeal to the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia finally decided the issue on September 12, 2023. It held that the non-commercial dissemination of these standards as incorporated by reference into law constitutes copyright fair use, and therefore cannot support liability for copyright infringement.

As we have observed on many occasions, copyright fair use is an unpredictable legal doctrine. Often, the outcome seems to be in the eye of the beholder – the judge or judicial panel – rather than the result of any predictive legal test. A recent example of this is Goldsmith v. Warhol: a federal district court held that Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo of Prince was fair use. The Second Circuit reversed, holding that it wasn’t. The Supreme Court upheld that ruling, but under a different rationale from the Second Circuit. Three courts, three different approaches to fair use. For another example see Final Thoughts On Google v. Oracle. The result is a confusing body of law that lacks predictability for the copyright community, both authors and the lawyers that are asked to advise them.

D.C. Circuit’s Holding in ASTM

While Warhol involved art and Oracle software, ASTM involved privately developed technical standards that had been incorporated into law “by reference.”

There is no question that in most cases technical standards are copyrightable – that is, they reflect sufficient originality to be protected by U.S. copyright law. Hence, without an affirmative defense Public Resource’s reproduction and distribution of ASTM’s standards infringed its copyrights. Public Resource’s defense was copyright fair use.

The D.C. Circuit applied – as it must – the four-factor fair use test:

Purpose and Character of the Use. Under the first factor it found that the “purpose and character“ of Public Resource’s nonprofit status favored fair use. Further Public Resource’s use of the standards – to provide a free repository of the law – is “transformative,” a key issue in any fair use case. While in most cases the term “transformative” involves changes to the work, here the court construed it to mean a transformative “use” of the work.

Nature of the Copyrighted Work. Factor two also favored fair use. Because the court viewed the standards as “factual” in nature – a conclusion we find questionable – it conclude that they “fall at best, at the outer edge of copyright’s protective purposes.” Factual works are often given “weak” or “thin” copyright protection, and because protection is weaker for such works, it’s easier to establish fair use.

Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used. Under factor three, although Public Resource copied the standards in their entirety, the court found that this was necessary in light of the purpose. “If an agency has given legal effect to an entire standard, then its entire reproduction is reasonable in relation to the purpose of the copying . . ..” This is not unusual in the context of copyright fair use – many fair use cases involve comprehensive copying. Oracle is a good example of this.

Effect of the Use Upon the Potential Market for or Value of the Copyrighted Work. Lastly, the fourth fair use factor required the court to consider the “market harm“ caused by Public Resource’s copying, including any substantially adverse impact on the “potential market“ for the original standards. While the court observed that it “seems reasonable” to suppose that economic harm might result, it found that the plaintiffs could not quantify past or future financial harms, relying instead on “conclusion, assertions and speculation.“ In any event, even if Public Resource’s free postings lowered the demand for the plaintiffs’ standards, this was outweighed by “the substantial public benefits of free and easy access to the law.“ The court concluded that the fourth fair use factor did not tip the balance one way or the other. But because the first three factors “strongly“ favored fair use, it found that Public Resource’s non-commercial posting of standards incorporated into law by reference is fair use.

Legal Precedents Favored Public Resource

The extent to which the law should be in the public domain is not a new issue for copyright law. In 2020 the Supreme Court held that annotations to Georgia’s official statutory code, as government edicts, were free from copyright. In that case the Court didn’t even reach fair use – it held that officials who “speak with the force of law” cannot claim copyright in the works they create in the course of their official duties.” Georgia v. Public Resource.

The lower courts have also weighed in on this issue. In Veeck v. Southern Building Code the Fifth Circuit relied on fair use to hold that model building codes adopted by reference could be copied. In Building Officials & Code Administration. v. Code Technologies, Inc. the First Circuit suggested that once a model building code has been adopted into law it is in the public domain, and remanded for further consideration.

Public Resource relied heavily on these cases on appeal, and indeed, these precedents put ASTM and its co-plaintiffs in an uphill battle heading into the appeal to the D.C. Circuit.

Copyright Fair Use Based On “Public Benefits”

While not explicitly identified in the Copyright Act, the “public benefit” theory of fair use prioritizes societal and cultural benefits in the application of copyright law. A recent example of this is the Supreme Court’s holding in Oracle v. Google. In this 2021 case the issue was whether Google’s use of Oracle’s Java API (Application Programming Interface) in its Android operating system constituted fair use. While Google copied all of Oracle API and used it commercially, the Court found fair use, based in part on the benefit to the software development industry and technical innovation. As the Court said, “we must take into account the public benefits the copying will likely produce.”

Similarly, in the 2015 Google Book Search decision, Author’s Guild v. Google, the Second Circuit recognized the substantial public benefits of Google’s project in concluding that Google’s verbatim copy of books was protected by fair use.

The D.C. Circuit’s ruling in the ASTM case follows this line of reasoning. Just as there is a public benefit in allowing software developers to use the Java API, and a public benefit in allowing the public to search copyright-protected books for relevant “snippets,” so does the publication of laws incorporated by reference benefit the public by making the law more accessible. However, as we discuss below, it did this at the risk of upsetting the delicate balance between the standards organizations and the governments that benefit from their works.

Was the “Public Benefits” Theory of Fair Use Properly Applied in ASTM?

While the D.C. Circuit’s holding allowing the unauthorized reproduction of standards may fall within the “public benefits” line of fair use cases, in our view there is a risk that the court misjudged the interplay between standards organizations, government entities, and public access. Any challenge to the delicate symbiotic private-government relationship risks injury to the public interest, which benefits from the creation of these standards. Based on our experience working with nonprofit standards organizations for decades, we fear that the D.C. Circuit underestimated this potential disruption.

Importantly, the court found insufficient an accommodation that many standards developers (including ASTM) have already put in place in response to Public Resource’s challenge. Specifically, they have created public “reading rooms” where every standard they have developed that has been incorporated into law by reference can be read, free of charge, online in read-only mode. The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) hosts an “IBR Standards Portal” offering one stop access to the incorporated by reference (IBR) standards of a dozen major standards organizations can be accessed, as well as links to another sixteen standards organizations reading rooms with links to their own IBR’d standards.

As noted, many standards organizations charge a fee for copies of their standards. In the case of many traditional standards developers, such fees comprise a major, or even the majority, of the budgets of the organizations. Developing standards is inherently time-consuming and expensive, and in some cases (e.g., organizations that develop building codes), most or all of the production of such organizations is referenced into law. In other cases, standards were never intended for referencing into law, but have been nonetheless, without notice to, or consent by, the organization that developed them. The revenues from sales and licensing are reinvested into research, development, and enhancement of new and existing standards. Respecting copyright protects the investments of these organizations in developing standards, ensuring they can fund their continuing operations and standards development and providing incentives to continue to create these essential public goods.

The unauthorized distribution by nonprofits risks reducing those revenues and incentives by offering a free alternative to purchasing or licensing the standards. This, in turn, risks slowing down the frequency of updating existing standards and innovating new ones, potentially leaving them outdated or less applicable to evolving industry needs.

This may prove to be the case if the implications of the decision extend beyond nonprofit vendors to for-profit companies. Some for-profit companies already do sell copies of standards without first paying for the rights to do so. It is difficult to see how the court’s rationale – finding fair use when a nonprofit engages in this behavior – does not extend to for-profit sales of standards.

Our bottom line takeaway: the implications of this decision on private standard-setting organizations and their business models may be far reaching. Hopefully, there may be a legislative solution that may provide relief. On March 17, 2023, Darrell Issa (R CA) introduced proposed amendments to amend the Copyright Act with bipartisan support from seven representatives from each party. If enacted, the bill would void a fair use defense against a claim of infringement of an IBR’d standard if that standard “is displayed for review in a readily accessible manner on a public website,” without cost.

We support this common sense ratification of the public reading room approach and hope that the bill is adopted.

American Society for Testing and Materials v. Public.Resource.Org., Inc. (D.C. Cir. Sept. 12, 2023).

by Lee Gesmer | Aug 28, 2023 | Copyright

In an previous post I focused on the AI “output” issue – who owns an AI model’s output? (Artificial Intelligence May Result In Human Extinction, But In the Meantime There’s a Lot of Lawyering To Be Done). I noted that this issue was pending in a lawsuit before the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia (Thaler v. Perlmutter).

The decision in this case was issued by Judge Beryl A. Howell on August 18, 2023. In her ruling Judge Howell made it clear that a creation born out of an artificial intelligence system cannot be copyrighted due to the lack of human creativity, the “sine qua non at the core of copyrightability.”

Background

In 2019 Stephen Thaler filed an unusual copyright application. Instead of a traditional artwork, the piece – titled “A Recent Entrance to Paradise” (the image appears at the top of this post) – identified an unusual ‘creator’ – the “Creativity Machine.” The Creativity Machine is an AI system invented by Thaler. In his application for registration Thaler informed the Copyright Office that the work was “created autonomously by machine,“ and his claim to the copyright was based on the fact of his “ownership of the machine.“

The Copyright Office, however, didn’t see it his way. Its position is that that copyright protections are reserved exclusively for works born from human ingenuity. See Copyright Registration Guidance: Works Containing Material Generated by Artificial Intelligence. On this basis it declined Thaler’s application.

Judge Howell’s Decision

Oscar Wilde photo in Burrow-Giles case

On appeal to the district court Judge Howell acknowledged that copyright law is “malleable enough to cover works created with or involving technologies developed long after traditional media.” A prime example of this is the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1884 decision in Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, holding that a photograph of Oscar Wilde was copyrightable despite use of a camera, since the camera was used to give “visible expression” to “ideas in the mind of the author.” However, the rationale in this case didn’t go far enough for Judge Howell. Her decision emphasized the foundational principle of copyright: human creativity –

The act of human creation—and how to best encourage human individuals to engage in that creation, and thereby promote science and the useful arts—[has been] central to American copyright from its very inception. Non-human actors need no incentivization with the promise of exclusive rights under United States law, and copyright was therefore not designed to reach them.

The Copyright Act itself leans heavily toward human-centric creation, with previous court decisions strengthening the court’s perspective. The case that has received much of the attention on this topic is Naruto v. Slater, where a photograph, though artistically noteworthy, wasn’t given copyright protection because it was taken by a monkey, not a human – “all animals, since they are not human,” lack standing under the Copyright Act.

Attempting to navigate this legal maze, on appeal Thaler presented a fresh angle. He argued that as the mastermind behind the AI, providing it with direction and instructions, he should be considered the rightful human author. But this theory had not been asserted in his original application for registration, and therefore was dismissed by the court: “here, plaintiff informed the register that the work was ‘created autonomously by machine,’ and his claim to the copyright was only based on the fact of his ‘ownership of the machine.'” Therefore, the court limited Thaler’s appeal to the question of whether a work generated autonomously by a computer system is eligible for copyright, and held that it was not.

Navigating Uncharted Waters: Future Implications

9th Cir in Naruto case: Monkey selfie not copyright-protected

The Thaler case sets a precedent: a creation made entirely by an AI, without human intervention, remains outside the protective bounds of the Copyright Act – at least for now. Not surprisingly, Thaler has announced that he will appeal this ruling to the D.C. Circuit. Onward and upward.

Moreover, this case leaves unaddressed a myriad of yet-to-be-answered questions:

- At what point, and to what extent – if at all – does human interaction with AI validate a creation as human-made?

- How do we gauge the originality of AI creations when these AI systems might have been trained using pre-existing works?

- Should the current structure of copyright be reformed to support and foster AI-involved creations?

These questions remain tantalizingly open, awaiting future exploration and legal interpretation. The ongoing debate about AI’s role in the world of creativity and copyright is just beginning.

Thaler v. Perlmutter (D. C. August 18, 2023)

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 15, 2023 | Copyright

A couple of people have asked me about the legal story behind Taylor Swift’s re-recording of her earlier albums.

Great question. In fact, she has re-recorded three of them.

This unusual story is a perfect “music copyright” teaching moment.

Why The Re-Recordings?

The background is a bit convoluted, but it arises out of an ugly split between Swift and her first recording company, Big Machine Records. Following the split Swift began releasing her re-recorded songs, Fearless (Taylor’s Version) and Red (Taylor’s Version) in 2021 and Speak Now (Taylor’s Version) in 2023.

Why did she re-record the songs on these albums? The gory details are discussed under the link above, but after the falling out with Big Machine, Swift decided to re-record the songs owned by it, apparently with the intention of diverting sales from her former recording company.

Swift’s popularity and financial resources allow her to do something few other artists could hope to undertake.

Copyright Law and Music

There is an important aspect of copyright law at the heart of what happened here. Every musical recording potentially has two copyrights – one in the musical work and one in each recording of the work. The musical work is the composition – the chords, melody and lyrics. Swift penned the songs on these three albums and as the author, retained ownership of these musical works. However, she assigned the recordings or “masters” to her recording company. Although she might earn royalties based on the sales and performances of these masters, she doesn’t own the copyright for them.

By not also assigning ownership of the musical works represented by the songs on the three albums, Swift retained what the music industry refers to as “publishing rights,” as in “hey, I own the publishing for this song, right?” Swift is therefore free to re-record them, as she has now done in the three “Taylor’s Version” albums.

Further Intricacies and Questions

It’s likely that there’s more to this story than has been revealed to the public. For instance, a contract between Swift and Big Machine may have temporarily delayed Swift from re-recording her songs. However, that’s more about contract law than copyright. The music industry, often a confusing maze, juggles both copyrights and contracts.

It’s likely that there’s more to this story than has been revealed to the public. For instance, a contract between Swift and Big Machine may have temporarily delayed Swift from re-recording her songs. However, that’s more about contract law than copyright. The music industry, often a confusing maze, juggles both copyrights and contracts.

The extent to which Swift is getting her hoped-for revenge is unknown – we don’t know the extent to which the re-recordings are cutting into sales of the original masters. And, no doubt there are many other legal complications that have not been made public. For example, assume a movie producer wants a “synchronization license” (a “sync” license) to use one of these recordings with a movie or TV show. The producer needs a license to both the master and the musical work. I can imagine Taylor Swift saying, “if you want a license to the musical work you need to license the new master from me as well.” This would cut out the owner of the first recording, and no doubt lead to threats of contractual interference. But is it legal? It probably is.

When I introduced the distinction between the copyrights in musical works and masters above, I said that “every musical recording potentially has two copyrights.” Why did I say “potentially”?

An example will illustrate why. Assume that in 2023 a symphony orchestra records and releases a performance of Antonín Dvořák’s NewWorld Symphony, composed in 1893. The copyright in the musical work has expired. Anyone is free to record this work. However, a new copyright applies to the new recording and will last for decades. Thus, only one copyright – the copyright in the master – exists in this scenario.

If you’re interested in the drama between Taylor Swift and her former record company, this Wikipedia entry has most of it.

Image credit: Eva Rinaldi https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Taylor_Swift_%286966830273%29.jpg

by Lee Gesmer | Apr 21, 2023 | Copyright

Software copyright is an important area of copyright law. However, it has proven devilishly difficult for the courts to apply. As the Second Circuit observed 30 years ago, trying to apply copyright law to software is often an “attempt to fit the proverbial square peg in a round hole.” Judges know this – I’ll never forget the time that Massachusetts Federal District Court Judge Rya Zobel, during an initial case conference in a copyright case, looked me in the eye and said, “we aren’t going to have to compare source codes in this case, are we Mr. Gesmer?” (We didn’t, the case settled soon afterwards).

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (the CAFC) has grappled with this challenge, most notably in its two controversial decisions in Oracle v. Google. (2014, 2018).

Now the CAFC has issued an important decision in SAS Institute, Inc. v. World Programming Limited (April 6, 2023; Newman dissenting). The issue in this case is one that I encountered in a copyright suit in Boston, so it’s of particular interest to me. More on that below.

SAS Institute and World Programming

SAS Institute is a successful software company. Its annual revenues exceed $3 billion, and it has more than 12,000 employees. Its statistical analysis software — the “SAS System” – is used in 3,000+ companies worldwide.

Success attracts imitation, and World Programming (now part of Altair) developed a “clone” of the SAS Software. SAS didn’t react kindly to the competition – it has conducted a more-than 10 year, multi-nation legal challenge, suing World Programming once in England and twice in the United States.

What makes SAS’s most recent copyright case against World Programming unusual is the subject matter. Most software copyright litigation involves the “literal elements” of computer programs – the “source” and “object” code – essentially the “written words” or the machine code (ones and zeros) of the software.

“Non-literal” Copyright Infringement

SAS v. World Programming, however, involved the “non-literal” elements of SAS’s system. The courts define “non-literal elements” as the structure, sequence, and organization and the user interface of software. Basically, anything other than the computer code. SAS alleged that World Programming illegally copied input syntax formats and output design styles – non-literal components of the SAS System.

The idea that non-literal components of a software program can be protected by copyright has been acknowledged since the 1980s. For the last 30 years most courts have followed the “abstraction-filtration-comparison” test (AFC test) established in the 1992 Second Circuit decision in Altai v. Computer Associates. The AFC test requires the court to (1) break a software program into its constituent parts (abstraction), (2) filter out unprotectable elements (filtration) and (3) compare the remaining protectable elements to the allegedly infringing work (comparison).

If this sounds challenging to you, you are right. However, relatively few cases have actually had to undertake the real-world application of this test to the non-literal elements of a software program. And, where they have the plaintiff has almost always lost.

The District Court Case

SAS filed this case in the Eastern District of Texas. The district court judge proceeded to apply the Altai AFC test by conducting a hearing to “filter out” unprotectable elements of the SAS software. Examples of unprotected elements include ideas, facts, information in the public domain, merger material, scènes à faire and conventional display elements. Case law has established that abstraction and filtration (steps 1 and 2 of the AFC test) is performed by the judge, not the jury.

The district court held what it termed a “copyrightability hearing” and implemented an alternating, burden-shifting framework in which SAS was required to prove a valid copyright and “factual copying.” The burden then shifted to defendant (World Programming) to prove that some or all of the copied material is unprotectable. The burden then shifted back to SAS to respond and persuade the court otherwise.

Think of this as a tennis volley in which the ball crosses the net three times.

SAS satisfied the first part of this test – it showed that it had a registered copyright, and that World Programming had copied some elements of the SAS System. However, World Programming responded with evidence that many of the non-literal components of the SAS System contained factual elements, elements that were not original to SAS or that were in the public domain, unprotected mathematical and method components, conventional display elements and merger elements. World Programming asserted that all of these components should be filtered out and excluded from step 3 of the AFC test – comparison of the two software programs.

At that point, under the judge’s burden shifting approach, the burden fell on SAS to respond and address these defenses.

Inexplicably, SAS failed to do this. The court stated –

SAS has not attempted to show what World Programming pointed to as unprotectable is indeed entitled to protection. . . . Instead, when the burden shifted back to SAS, it was clear SAS had done no filtration; they simply repeated and repeated that the SAS System was “creative.” . . . SAS’s failures have raised the untenable specter of the Court taking copyright claims to trial without any filtered showing of protectable material within the asserted work. This is not a result that this Court can condone. These failures rest solely on SAS and the consequences of those failures necessarily rest upon SAS as well.

The district court then dismissed the case. SAS appealed to the Federal Circuit – a court that is notoriously pro-copyright. (See the two Oracle decisions linked to above). SAS likely planned for any appeal to go to the Federal Circuit by asserting patent infringement against World Programming and later dropping its patent claims. Nevertheless, that was enough to give the Federal Circuit jurisdiction over any appeal.

Appeal to the Federal Circuit

On appeal the central question was procedural: Was it SAS’s burden to prove that the copied elements were protectable, or was it World Programming’s burden to prove that they were not? In other words, the issue was who bears the burden of proving, as part of the filtration analysis, that the elements the defendant copied are unprotectable – the plaintiff (copyright owner) or the defendant (alleged infringer)?

The Federal Circuit was not impressed with SAS’s arguments on appeal. It noted that rather than participate in the steps required by the Altai AFC test, SAS “failed or refused” to identify the constituent elements of the SAS software that it claimed were protectable. Instead, it argued that its software was “creative” and that it had provided evidence that World Programming had engaged in “factual copying.” But it provided no evidence in relation to the “filtration” step under the 3-part Altai AFC test.

The Federal Circuit found the trial court judge’s procedure to be appropriate: “a court may reasonably adopt an analysis to determine what the ‘core of protectable expression’ is to provide the jury with accurate elements to compare in its role of determining whether infringement has occurred.” The court concluded that SAS failed to “articulate a legally viable theory” and affirmed dismissal.

In other words, to continue the tennis analogy, SAS served the ball (showed that it had copyright registrations and that World Programming had copied some elements). World Programming returned the ball, introducing evidence that many of the elements SAS had identified were unprotected by copyright, and needed to be “filtered out” before the SAS and World Programming software programs were compared. However, SAS was unable to return that volley – “The district court found that SAS refused to engage in the filtration step and chose instead to simply argue that the SAS System was ‘creative.’”

20-20 Design v. Real View – Same Issue, No Controversy

While this is an important software copyright case and will be used defensively by copyright defendants in the future, it caught my attention for a second reason, which is that I dealt with the same issue in 20-20 Design v. Real View LLC, a copyright infringement case I tried to a jury in Boston in 2010. That case dealt with the graphical user interface of a software program – “nonliteral” elements of the software. Like World Programming in the SAS case, Real View allegedly created a “clone” program, but the cloning didn’t involve the source or object code, only parts of the graphical user interface.

Massachusetts Federal District Court Judge Patti Saris ordered 20-20 Design, the plaintiff/copyright owner, to identify the elements of its software that it claimed had been infringed. Unlike SAS, 20-20 Design complied. It provided a list of 60 elements, and the court held what Judge Saris called (by analogy) a “Markman”-style evidentiary hearing, which included evidence and testimony from experts on both sides. In effect, this was the “copyrightability hearing” held by the court in the SAS case.

Judge Saris then issued a copyrightability decision holding that almost all of the items were not individually protectible. They could, however, be protected as a “compilation.” However, she ruled that as a “compilation,” the plaintiff-copyright owner was required to prove that the defendant’s software interface was “virtually identical” – a much more difficult standard to meet than the “substantial similarity” standard applied in most copyright litigation.

(Humble brag: 20-20 Design was seeking damages of $2.8 million. However, the “virtually identical” standard proved to be its downfall. Without going into detail, suffice it to say that after a 10-day jury trial and post-trial motions the judge entered judgment for 20-20 Design against Real View (my client) in the amount of $4,200. (link)

When I read the decision in SAS v. World Programming I immediately related it to the 20-20 Design/Real View case, but I couldn’t recall how Judge Saris had allocated the burden-of-proof. When I refreshed my memory I realized why – the judge and the parties never discussed this issue. It seems that everyone assumed that the plaintiff-copyright holder (20-20 Design) had the burden of proof. After 20-20 identified the copied elements Real View argued that most of them should be filtered out and 20-20 Design (unlike SAS) responded with counter arguments. In other words, the ball went over the net three times, and the judge was able to apply the Altai AFC test and “filter” 20-20’s software before trial.

Thinking back on how smoothly this procedure went in my case, it’s difficult for me to imagine how SAS chose the strategy that cost it the World Programming case, unless this case was just an attempt to outspend a smaller competitor and drive it out of the market with litigation expenses. SAS is a multi-billion-dollar company. Its lawyers are highly experienced. Why SAS chose a case strategy that seemed doomed to failure is a bit of a mystery. One possibility is that SAS knew that if it identified the elements it would be forced into a copyright compilation theory that requires proof that the infringing work is “virtually identical” to plaintiff’s work, a burden that SAS believed it could not satisfy. Another is that it gambled that the Federal Circuit – which is notoriously protective of copyright owners – would see the law its way and reverse the district court. We will never know.

Although it remains a mystery why SAS chose a case strategy that seemed destined to fail, the SAS v. World Programming decision has important implications for software copyright law. It clarifies the burden-shifting process and emphasizes the importance that the plaintiff be fully prepared to engage in the Altai AFC test’s filtration step.

Will SAS appeal this decision to the Supreme Court? Given the resources that SAS has dedicated to its litigation with World Programming over the last decade it seems likely that it will. While I view it as doubtful that the Supreme Court will hear this case, you never know.

SAS Institute v. World Programming (Fed. Cir. April 6, 2023)

by Lee Gesmer | Mar 6, 2023 | Copyright

There are a number of computer programs and websites that will allow you to create an image using artificial intelligence. One of them is Midjourney. You can see some of the Midjourney AI-generated art here.

Kris Kashtanova used Midjourney’s generative AI tool to create a comic book titled Zarya of the Dawn. She submitted the work to the Copyright Office, seeking registration, and the Office issued the registration in September 2022. However according to the Copyright Office Ms. Kashtanova did not disclose that she used artificial intelligence to create Zarya.

Soon afterwards the Office became aware – via a reporter’s inquiry and social media posts – that Ms. Kashtanova had created the comic book using artificial intelligence. The Office reconsidered the registration and, after much correspondence and argumentation with Ms. Kashtanova’s attorneys, canceled the registration, concluding that:

. . . the images in the Work that were generated by the Midjourney technology are not the product of human authorship. Because the current registration for the Work does not disclaim its Midjourney-generated content, we intend to cancel the original certificate issued to Ms. Kashtanova and issue a new one covering only the expressive material that she created.

Image from Zarya

This conclusion is the denouement in a lengthy letter from the Copyright Office analyzing the copyrightability of the images contained in the Zarya comic in detail in light of how Midjourney creates images. In correspondence with the Copyright Office Ms. Kashtanova argued that she had provided “hundreds or thousands of descriptive prompts” to Midjourney to generate “as perfect a rendition of her vision as possible.” However, based on how Midjourney creates images – essentially via a random mechanical process, notwithstanding the prompts of the human “mastermind” – the Copyright Office concluded that she was not the “author” of the resulting images for copyright purposes. The Copyright Office reasoned that “unlike other tools used by artists” (such as Adobe Photoshop), Midjourney generates images using prompts in an “unpredictable way.” “Because of the significant distance between what a user may direct Midjourney to create and the visual material Midjourney actually produces,” Ms. Kashtanova did not have enough control over the final images generated to be the “inventive or mastermind” behind the images.

Here are some takeaways from this decision.

First, artists using generative AI to create images should not assume that they own a copyright in the images. At present the Copyright Office appears firmly committed to its position that they do not, and until there are court decisions to the contrary, or Congress amends the Copyright Act to accommodate these works, the better practice is to assume no protection.