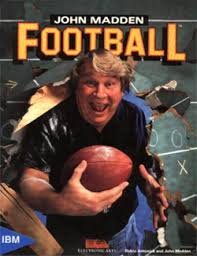

I was surprised when I read the Ninth Circuit’s recent decision in Antonick v. Electronic Arts, Inc. (9th Cir. Nov. 22, 2016). In that case the plaintiff alleged copyright infringement against EA* based on copying of computer source code for the John Madden Football game, but failed to introduce the source code into evidence, choosing instead to rely solely on expert testimony to prove copying.

*[footnote] Technically speaking, this was a breach of contract case. However, the contract between Antonick and EA stated that Antonick would receive royalties on the sale of any “derivative work”, as that term is defined under U.S. copyright law. As a result, the parties and the courts applied copyright law to determine whether EA had breached its royalty agreement with Antonick.

This was an enormous risk, and it doomed Mr. Antonick’s case. The Ninth Circuit panel held:

Antonick’s claims rest on the contention that the source code of the Sega Madden games infringed on the source code for Apple II Madden. But, none of the source code was in evidence. The jury therefore could not compare the works to determine substantial similarity.

Expert testimony alone was not sufficient, the court ruled. However, even if expert testimony had been sufficient, Antonick’s case failed: the expert testimony presented by Antonick related to how the games appeared to users (the user interface), not the source code. Antonick’s case was based on similarities between the source code of the products, not the user interface.

Maybe there was a good reason that Antonick’s lawyers didn’t introduce the source code into evidence. Perhaps the original source code (which is decades old) was no longer available, and Antonick was trying to skirt this issue; if so this isn’t apparent from the opinion. I hope, for Antonick’s sake, that his lawyers didn’t think they could prove copying of source code by focusing on the user interface of the programs, since similarities in interfaces don’t necessarily mean the source code that generates them are the same or similar.

Trial lawyers know that one goal at trial is to introduce as much evidence into the record as possible, to avoid just this kind of outcome. As long as evidence is in the record, a party can point to it to support its case even if (as likely was the case here), the evidence is computer source code incomprehensible to the jury. A document may be incomprehensible to the jury, but as long as it is in evidence, the courts will adopt the fiction that that the jury considered it in reaching its verdict.

In this case Antonick prevailed in a jury trial, but the judge set the verdict aside post-trial, based on his failure to introduce the two works. Antonick appealed, but lost on appeal.

Antonick went the last mile to try to save his case on appeal, retaining famed copyright lawyer and treatise author David Nimmer (“Nimmer on Copyright”) to argue his case. This was unsuccessful.

Here is the video of oral argument before the 3-judge 9th Circuit panel. Nimmer’s argument begins at :20 in the video, and his rebuttal testimony begins at 1:10.

The district court’s opinion, which discusses the plaintiff’s failure to introduce the works at issue into evidence in more detail, is available here.