by Lee Gesmer | Dec 7, 2025 | Employment

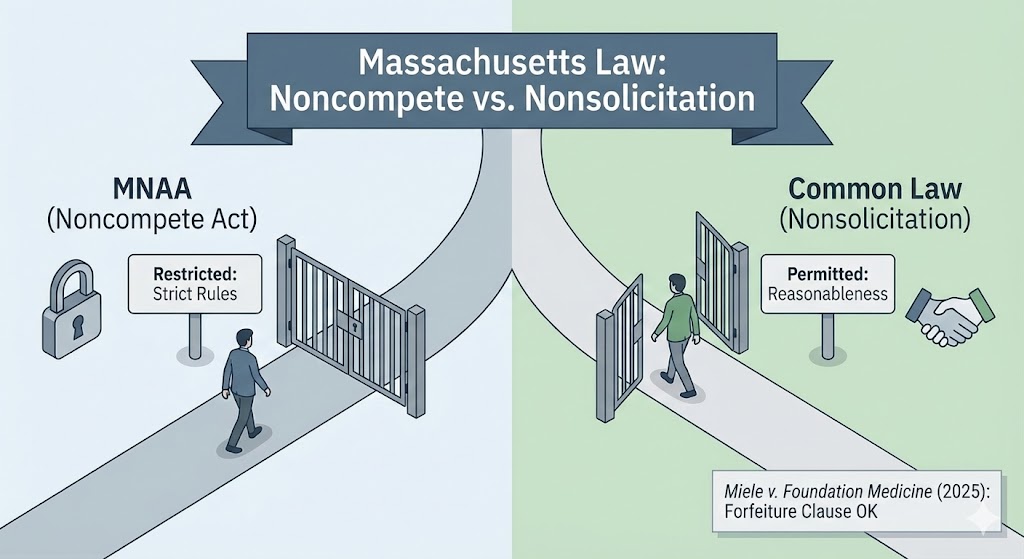

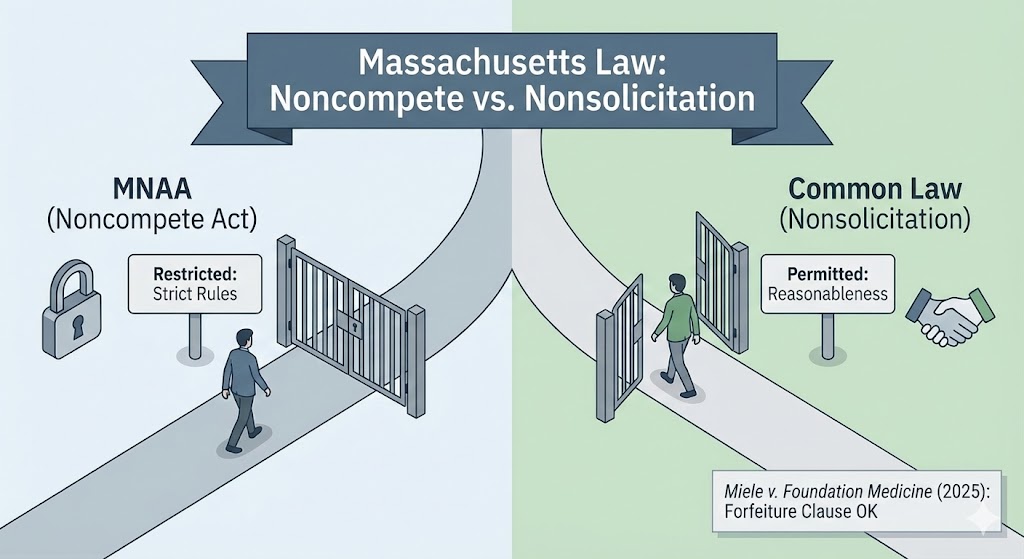

When the Massachusetts Noncompetition Agreement Act (MNAA) took effect in October 2018, I described the law in detail and wrote that employers and employees were entering “a new era” in noncompete law. The statute imposed formalities, created new employee protections, and limited the enforceable duration of noncompetes. But it also drew a set of carefully worded exclusions – most notably for nonsolicitation agreements. I predicted that those exclusions would become critical as employers adjusted to this new law.

Seven years later, the Supreme Judicial Court has now decided its first significant case interpreting the statute, Miele v. Foundation Medicine, Inc. (2025). The decision answers a narrow question, but it carries substantial practical consequences. The court held that the MNAA does not apply when an employer conditions severance pay on compliance with an employee-nonsolicitation covenant. In other words, adding a forfeiture-of-benefits clause to a nonsolicit does not convert it into a noncompetition agreement.

What the MNAA Regulates – And What It Doesn’t

The MNAA regulates agreements that bar a former employee from engaging in post-employment competition. To be enforceable, such agreements must satisfy a gauntlet of statutory onerous requirements: advance notice, a written agreement signed by both parties, the right to consult counsel, a one-year limit on duration (with narrow exceptions), and “garden leave” or other agreed-upon consideration.

And, importantly, the MNAA includes “forfeiture for competition” agreements under the definition of noncompetition agreements. This was designed to prevent employers from avoiding the statute’s requirements by replacing a noncompete with a compensation-forfeiture clause that accomplishes the same result. In other words, employers should not be able to sidestep limits on noncompetes by changing the mechanism of enforcement.

The statute is sufficiently burdensome that employee noncompete agreements, once a routine feature of employment contracts in Massachusetts, are now seldom used.

But the statute does not sweep in every type of restrictive covenant. Its definition of “noncompetition agreement” excludes several categories, including:

- Employee and customer nonsolicitation covenants

- Confidentiality and intellectual-property assignment provisions

- Covenants linked to the sale of a business

As I noted in 2018, those exclusions matter. A well-drafted nonsolicitation clause can serve much of the protective function that noncompetes historically played. The MNAA left those covenants to be governed by common-law reasonableness standards rather than the statute’s rigid framework.

The Dispute in Miele

Susan Miele signed an employee-nonsolicitation agreement when she joined Foundation Medicine in 2017. When she left the company in 2020, she entered into a “transition agreement” providing substantial severance benefits. That agreement incorporated the earlier nonsolicitation covenant and added a forfeiture clause: if she breached any of her continuing obligations, she would forfeit unpaid benefits and repay benefits already received.

After Miele joined a competitor, Foundation Medicine alleged that she solicited several FMI employees during the one-year restricted period. The company stopped payments and demanded repayment. Miele sued, arguing that the forfeiture provision was an unenforceable “forfeiture for competition” agreement subject to the MNAA.

She took this argument all the way to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and lost.

The SJC’s Holding: A Nonsolicitation Clause Remains a Nonsolicitation Clause

The SJC’s analysis turned on the statute’s definitions. The MNAA:

- Excludes nonsolicitation agreements from the category of noncompetition agreements; and

- Defines forfeiture-for-competition agreements as a type of noncompetition agreement.

Given those two premises, the court held that a forfeiture triggered by a breach of a nonsolicitation covenant is not a “forfeiture for competition agreement” under the MNAA. The forbidden conduct was solicitation, not competition itself. Because the underlying covenant falls outside the statute, the forfeiture remedy does not bring it back within the statute’s scope.

In short: the presence of a forfeiture provision does not change the legal identity of the underlying restrictive covenant. If the covenant is a nonsolicitation clause, the MNAA does not apply.

Implications Going Forward

Miele gives employers and employees much-needed clarity, and it confirms several practical realities about the MNAA:

- Nonsolicitation provisions remain outside the statute, even when backed by serious financial consequences. A severance agreement that conditions payment on compliance with a nonsolicitation covenant does not trigger the MNAA merely because the remedy is forfeiture or repayment. These provisions will continue to be governed by pre-2018 common law.

- The MNAA’s reach depends on the nature of the restricted activity, not the chosen remedy. If an agreement penalizes an employee for working for a competitor, it is a forfeiture-for-competition agreement subject to the statute. If it penalizes solicitation, it is not. The drafting focus rests on the conduct being restricted, not the mechanism of enforcement.

- Common-law reasonableness remains the governing framework for nonsolicitation covenants. Duration, scope, legitimate business interest, and employee role still matter. Parties should expect future litigation over what counts as “solicitation,” a concept the common law has never cleanly defined. I wrote about this perplexing topic more than ten years ago in Nudge, Nudge, Wink, Wink – Are You “Soliciting” in Violation of an Employee Non-Solicitation Agreement?

- Separate statutes still matter. Miele does not insulate forfeiture clauses from scrutiny under the Massachusetts Wage Act or other employment statutes. Severance structured as earned compensation, for example, may present Wage Act issues if subject to forfeiture.

- Expect heavier reliance on nonsolicitation + severance-forfeiture structures. The decision validates a drafting strategy employers began adopting after 2018: use narrower covenants that avoid the MNAA altogether, coupled with meaningful financial incentives for compliance.

Conclusion

When the MNAA was enacted, the open question was how far courts would go in applying its protective rules beyond traditional noncompetes. Miele provides a clear boundary: the MNAA governs restraints on competitive employment, not every restrictive covenant that may influence post-employment behavior. Nonsolicitation clauses, even with substantial economic consequences attached, remain on the common-law side of the line.

Employers will undoubtedly make fuller use of that space. Employees and their counsel will scrutinize whether a provision labeled “nonsolicitation” is in substance a broader restriction. And the statute will continue to generate interpretive questions as parties test its edges.

by Lee Gesmer | Nov 21, 2023 | Corporate Law, Employment

OpenAI fired Sam Altman, its CEO-founder, the afternoon of November 17, 2023. In the corporate chaos that followed the company went through two acting CEOs within three days. By the end of the day on Monday, November 20, Altman and other key executives at OpenAI were hired by Microsoft. Immediately following this 700 employees – practically the whole company – signed a letter threatening to quit unless the Board resigns and Altman is reinstated.

It’s hard to imagine how this termination could have been handled more ineffectively. It is an exemplar of exactly how NOT to fire your CEO.

However, all the OpenAI Board members had to do was ask their own product – ChatGPT – how to go about terminating Altman. Here’s my query to ChatGPT-4, and it’s response –

PROMPT TO GPT:

I am on the Board of Directors of a closely held California-based corporation. We are considering terminating our CEO. Please tell me in

To provide better governance and ensure rational decision-making, GPT-5 will join the new OpenAI Board of Directors

detail what steps we should take to prepare for and execute this termination. Take into consideration that my company is very high profile – we are a cutting-edge technology company that receives a lot of attention from the press and the technology industry. Our CEO is one of the founders of the company, and he is effectively “the face” of the company. He is frequently interviewed by the industry press and often appears at industry conferences and events to talk about our products. We have many partnerships with other companies and the CEO has been instrumental in forming those partnerships. While we are a bit unsure about this, we think that many of our key employees respect the CEO and may be loyal to him

CHATGPT-4 RESPONSE (my comments in italics and [brackets]):

Given the high-profile nature of your company and the CEO’s prominent role as a founder and the face of the company, the process of terminating the CEO requires additional layers of consideration and caution. Here are detailed steps tailored to your situation:

Preliminary Confidential Discussions: Initiate confidential discussions among the Board of Directors to thoroughly assess the reasons for considering termination and the potential impact on the company. Given the CEO’s prominence, it’s essential to evaluate the risks and benefits of this action carefully. [OpenAI board appears not to have done this]

Legal Consultation: Engage legal counsel experienced in high-profile executive terminations and corporate law. They can provide advice on contractual obligations, potential legal risks, and strategies for minimizing legal exposure, especially if the CEO is also a shareholder or has a significant stake in the company. [No information on whether Altman has an employment agreement with OpenAI or what its terms are. Note, however, that noncompete restrictions are not enforceable under California law, and therefore Altman and the other OpenAI employees cannot be prevented from going to work at Microsoft for this reason. There may, however, be trade secret issues in this fact pattern

Review Employment Agreement and Corporate Bylaws: Scrutinize the CEO’s employment contract and the corporation’s bylaws. These

Employee Letter to OpenAI Board

documents will guide the legal and procedural aspects of the termination process, including any ‘for cause’ conditions, severance terms, and required board approvals. Conduct a risk assessment focusing on potential repercussions within the technology industry, impact on partnerships, employee morale, and public perception. This assessment should consider the possibility of the CEO’s departure affecting key relationships and projects. [The OpenAI board either failed to do this, or completely miscalculated]

Internal Alignment: Ensure alignment and consensus within the Board of Directors. Given the CEO’s foundational role in the company, board members must be unified in their decision and prepared for the subsequent steps. [Ilya Sutskever, one of the Board members that voted to terminate Altman on Nov. 17, signed the employee letter on Monday Nov. 20]

Plan for Succession and Transition: Develop a succession plan that includes identifying an interim CEO or a successor. This plan should address how to maintain continuity in leadership and reassure employees, partners, and stakeholders about the company’s stability and future direction. [OpenAI announced an interim CEO on Friday – Mira Murati – and on Monday replaced her with a person brought in from outside the company. Over a period of four days OpenAI had three CEOs]

Communications Strategy: Formulate a comprehensive communications strategy. This should include internal communication to employees, as well as external communication to the press, industry partners, and stakeholders. The message should be crafted to maintain the company’s reputation and market confidence. [Internal/external communications were almost nonexistent]

employees, as well as external communication to the press, industry partners, and stakeholders. The message should be crafted to maintain the company’s reputation and market confidence. [Internal/external communications were almost nonexistent]

Managing Employee Sentiment: Prepare for potential fallout among employees who may be loyal to the CEO. This could involve individual discussions with key team members, departmental meetings, and ensuring that HR is equipped to handle any concerns or unrest. [Seems not to have been done at all]

Board Approval and Documentation: Formalize the decision with a board vote and document the process meticulously. This documentation is crucial for legal compliance and for maintaining a record of the decision-making process. [Outside of the board, no one seems to know why Altman was fired]

Executing the Termination: Plan the termination meeting with the CEO carefully, considering the timing, location, and who will be present. The conversation should be handled with respect and sensitivity, acknowledging the CEO’s contributions to the company. [Termination was done via Google Meet, a video service similar to Zoom]

Public Announcement: Coordinate the public announcement of the CEO’s departure with the communications strategy. This announcement should be respectful and align with the narrative agreed upon by the board. [The board didn’t have a narrative]

Post-Termination Steps: Monitor the company’s internal and external environment after the termination. Be prepared to manage any unforeseen consequences, including media inquiries, market reactions, and internal dynamics.

After the termination, review the company’s policies, leadership structure, and strategic direction. This is an opportunity to learn from the experience and strengthen the company’s governance and leadership practices.

Throughout this process, the key is to balance legal and procedural diligence with sensitivity to the human and cultural aspects of this significant change. The termination of a high-profile CEO can have far-reaching implications, and managing it effectively requires a thoughtful, strategic approach.

– end of GPT response –

by Lee Gesmer | Jun 24, 2021 | Employment, Trade Secrets

Every Massachusetts lawyer that drafts a civil complaint wonders – or should wonder – “can I allege 93A in this case?”

This law, M.G.L. c. 93A, is the Massachusetts unfair competition statute. It makes illegal “unfair and deceptive” acts and practices in the consumer and business contexts. The law is attractive to plaintiffs because it is one of the few state laws that provides the prospect of double or treble damages, as well as attorney’s fees.

What is “unfair and deceptive”? There are many cases where the courts attempt to parse out what conduct falls under 93A. It’s complicated, and there is a substantial body of 93A jurisprudence. The legal standards are beyond the scope of this post, but to get a sense for how the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) approaches this take a look at the SJC decisions in Morrison v. Toys “R” Us, Inc. and Aspinall v. Philip Morris Cos.

Because the law is largely judge-created, unless they follow c. 93A law closely most lawyers aren’t fully up to speed on the nuances of 93A and recent developments. And if you don’t assert 93A in your complaint, you might be deemed to have waived it if you try to add it later. What if the law changes between the date you file and the date you are challenged on it? You may be out of luck.

Given these factors many lawyers will include a 93A count almost reflexively, thinking that they’ll worry about the viability of the claim later, if and when the defendant challenges it. You’ll often see a 93A count in even the most routine cases, where it is eventually dropped or dismissed before trial.

There are a number of limitations on 93A, and one important limitation is that the illegal conduct must take place “in the conduct of any trade or commerce.” Based on this language the courts have held 93A to be inapplicable in the employment relationship. An employer-employee dispute is considered an “internal” business dispute outside “trade or commerce.” As a result of a series of decisions applying this doctrine, it is near-black letter law that 93A cannot be claimed by an employer against an employee, whether the employee’s violation occurs during or after the employment relationship. One well-known example of this is in the area of noncompete law – even though an employee’s breach of a noncompete may take place after employment ends, it is still considered an employer-employee dispute arising out of the employment relationship, and 93A does not apply.

Traditionally, under Massachusetts law, the act of misappropriating a trade secret by an employee falls under this restriction if the misappropriation occurs during the employment relationship. However, the courts have struggled with this doctrine, attempting to distinguish intra-employment conduct (which is exempt) from post-employment conduct (which may not be exempt).

The most recent decision in the line of employee misappropriation-93A cases is Governo Law Firm LLC v. Bergeron (2021). In this case six attorney-employees of the Governo law firm secretly downloaded proprietary information belonging to the firm and used that information when starting a new firm.

You’d think lawyers would know better.

At trial the jury returned a verdict for $900,000 in favor of Governo Law on the claims of conversion, breach of the duty of loyalty, and conspiracy.

However, Governo Law was unhappy with several aspects of the trial, one of which was that the judge instructed the jury that Chapter 93A did not apply to anything the defendants did while still employed by Governo, and the jury ruled against Governo on its 93A claim. This cost Governo Law the potential for double or treble damages and attorneys fees.

Governo Law appealed, and it won on this issue – the SJC reversed and sent the case back for a new trial on the 93A claim. The court fudged the distinction between the attorneys’ conduct during employment and afterwards. The heart of its holding is as follows:

[T]he 93A, claim required the jury to consider that the defendants stole the plaintiff’s materials in order to determine whether the subsequent use of these materials was unfair or deceptive. . . . where an employee misappropriates his or her employer’s proprietary materials during the course of employment and then uses the purloined materials in the marketplace, that conduct is not purely an internal matter; rather, it comprises a marketplace transaction that may give rise to a claim under 93A . . . . That the individuals were employees at the time of the misappropriation does not shield them from liability under 93A, where they subsequently used the ill-gotten materials to compete with their now-former employer.

This holding is not entirely new law – the state appeals court reached similar decisions in 2011 and 1984. (Specialized Tech. Resources, Inc. v. JPS Elastomerics Corp. (2011); Peggy Lawton Kitchens, Inc. v. Hogan (1984)). The Superior Court has also issued decisions on this issue. However, this is the first time the issue has reached the state supreme court, and it’s an important new landmark in Massachusetts 93A law. Whether it will lead to further erosion of employee 93A immunity in other contexts where the defendant’s conduct straddles the line between employee and non-employee remains to be seen. It may be that any illegal conduct during employment that will shed light on a former-employee’s post-employment conduct may now be admissible under the rationale used by the SJC in this case.

Governo Law is now entitled to a new trial, and this time the jury will be free to consider the six attorneys’ conduct while still employed by Governo Law in considering whether their subsequent use of the converted materials was an unfair or deceptive act. Exactly how the judge will instruct the jury on 93A remains to be seen – the SJC did not provide directions on this issue. However, the SJC opinion makes clear that the jury will be able to consider the fact that the attorneys stole Governo Law’s proprietary information, and regardless of whatever precautions the judge may take in the jury instructions, it’s hard to believe that jurors will not conflate employment conduct (stealing proprietary information) with post-employment conduct (using that information).

Governo Law goes into its 93A retrial (assuming no settlement) with a strong upper hand.

Governo Law Firm LLC v. Bergeron, 487 Mass. 188 (2021).

by Lee Gesmer | Feb 19, 2016 | Employment

Few things anger employers more than learning that an employee who has been terminated has, before leaving, copied confidential documents. Courts often view this as an equitable justification for enforcing a covenant not to compete that might otherwise be “on the line” legally – maybe enforceable, maybe not.

But what if an employee copies confidential documents and does nothing with them? In other words, doesn’t give them to a competitor or use them in a way harmful to the employer? If the employer discovers this after the employee has left, does it justify declaring that the employee is being terminated “for cause” (retroactively) and denying him the one year of severance his employment agreement had promised him when he was terminated “without cause”?

This was the issue in Eventmonitor v. Leness, which (rather oddly) went all the way to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. The precise issue was whether the employee had engaged in a “defalcation of company assets.” According to the employment agreement, “defalcation” was a basis for terminating the employee for cause and denying him severance payments. (The court chose not to grapple with the question of whether this could be done retroactively, as Eventmonitor tried to do, since a ruling on that issue was not necessary to decide the case).

However, “defalcation” was not defined in the employment agreement. The court decided that “in ordinary usage defalcation requires at least a temporary misuse or deprivation of the use or value of an asset.” Mr. Leland had not deprived Eventmonitor of its electronic files (he didn’t delete them, he copied them), and therefore he was not guilty of “defalcation.” Leland won.

One troubling postscript to this case is how long it took to resolve. It took five years for the case to go to trial, and eight years to be resolved completely through the appeals process. One can only hope the Massachusetts courts are able to do better than that. Eight years is a long time to wait to decide a case where only one word needs to be interpreted.

Eventmonitor v. Leness (Feb. 4, 2016 Mass.).

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 7, 2013 | Employment

Note: If you are unable to view this document on your computer, please click here.

[scribd id=151388882 key=key-2f825adp081om3h7j13c mode=scroll]

by Lee Gesmer | Jul 2, 2013 | Employment, Noncompete Agreements

Two note-worthy decisions have emerged from AMD v. Feldstein, a trade secret case pending in federal district court in Massachusetts. At the heart of the case is the conduct of several AMD employees who left to work for Nvidia Corporation. Inexplicably, they copied and took with them huge amounts of AMD data, actions which earned them a preliminary injunction in the first of two opinions, dated May 15, 2013.

However, in the May 15th decision Massachusetts federal district court judge Timothy Hillman also addressed the thorny issue of what constitutes a “solicitation” in violation of a non-solicitation agreement, and specifically solicitation of employees (as opposed to customers) of the former employer.

The employee non-solicitation provisions in this case were fairly standard. For example, Feldstein’s provided that:

during [Feldstein’s] employment with [AMD] and for a period of one year following the termination of [Feldstein’s] employment, whether voluntary or involuntary, [Feldstein would] not hire or attempt to hire an employee of [AMD], or directly or indirectly solicit, induce or encourage an employee of [AMD] to leave his or her employ to work for another employer, without first getting the written consent of an Officer of [AMD].

However, just what kinds of behavior violate such a provision, and which do not?

Clearly, expressly asking or encouraging an AMD employee to leave AMD would do so (“you should leave AMD and come to work for Nvidia with me – you can make much more money there, and they have chair massages every day!”). But what if Feldstein, on his last day of work at AMD, tells another employee “I’m moving to Nvidia” and winks? What if, after he’s at Nvidia, he has lunch with a former co-worker at AMD and raves about how much he likes his new job, nothing more? What if, once Feldstein is at Nvidia a former co-worker at AMD approaches him and asks him questions about salary and working conditions at Nvidia, and whether there are any more job openings, and he does nothing more than answer these questions? What if Feldstein encourages an AMD employee to move to Nvidia, but the employee was unhappy at AMD, and was planning to leave in any event? The permutations are almost endless.

These examples pose perplexing problems for employers and employees alike, who must try to navigate a thin line between legal and illegal behavior.*

*As the Massachusetts Appeals Court stated in a case involving the alleged solicitation of customers, “as a practical matter, the difference between accepting and receiving business, on the one hand, and indirectly soliciting on the other, may be more metaphysical than real.” (Alexander & Alexander, Inc. v. Danahy, 1986).

There is not a lot of law to help sort out these issues. As Judge Hillman points out, “much of the case law on solicitation in Massachusetts deals with former employees soliciting customers from their former employers,” not soliciting other employees. However, he noted that “colleagues can generally be expected to have even closer personal relationships than do employees and customers; and wherever closer working relationships are, courts must bear in the mind the fact that solicitation can be quite subtle.”

Needless to say, the parties in the case took opposing views. AMD argued for something close to a “wink test”– if Feldstein says he is leaving AMD to work at Nvidia and winks at another employee he has solicited. The former employees in the case argued that AMD should be required to prove that they took “active steps to persuade” an employee to leave, and even then they were not soliciting if the person were planning to leave anyway.

Rejecting these extreme positions Judge Hillman formulated the following tests:

I will define solicitation as follows. Direct solicitation is what might be seen as traditional solicitation, encompassing any active verbal or written encouragement to leave AMD, even if not intended to harm AMD. Due to the personal relationships that develop between colleagues, liability for indirect solicitation requires a more context-sensitive inquiry. …subtle hints and encouragements … can constitute indirect solicitation. However, to preserve the public’s interest in free personal communications, such solicitation should only be found where the finder-of-fact is satisfied that the solicitor actually intended to induce the solicitee to leave AMD.

Given the paucity of precedent on indirect solicitation in Massachusetts, this decision may be the best guide to the law of employee solicitation in Massachusetts at present.* However, the definition of “indirect solicitation” is problematic: given that a former employee accused of indirect solicitation is unlikely to admit illegal intent, it may be very difficult for the former employer to prove the requisite level of intent in court. Absent overt encouragement in the form of testimony or “smoking gun” emails, what chance does the employer have of proving the “actual intent” required by this test? Under this definition “nudge, nudge, wink, wink” may be safe for the former employee.

*A caveat: this decision was issued by a federal court, not a state court. The decision may carry relatively little weight with a state court judge, who is not bound by federal court decisions on Massachusetts law. The state courts are the final arbiters of state law.

An obvious conclusion to be drawn from this case is that non-solicitation clauses (at least as applied to employees), are weak tea. A potentially more effective way of preventing an ex-employee from luring employees away to a competitor (in most states, but not all) is indirectly, through a non-compete agreement. Although non-competes have their own set of enforcement problems (see, for example, this recent post), they have fewer problems than non-solicitations.

I’ll be writing about the second important issue to emerge out of this case in a separate post.

AMD v. Feldstein (D. Mass. May 15, 2013)

by Lee Gesmer | Dec 13, 2012 | Contracts, Employment

A lot of people blogged for The Huffington Post for free between 2005 and 2011. But after Huffpost was sold to AOL for $315 million in 2011, they had second thoughts about their generosity. They filed a class action seeking compensation for their work based on claims of unjust enrichment and deceptive business practices, seeking one-third of that money for the bloggers. The trial court, and now the Second Circuit, rejected their claims. As the Second Circuit stated early this week in Tasini v. AOL (2d Cir. Dec. 12, 2012):

Plaintiffs’ basic contention is that they were duped into providing free content for The Huffington Post based upon the representation that their work would be used to provide a public service and would not be supplied or sold to “Big Media.” Had they known that The Huffington Post would use their efforts not solely in support of liberal causes, but, in fact, to make itself desirable as a merger target for a large media corporation, plaintiffs claim they would never have supplied material for The Huffington Post.

The problem with plaintiffs’ argument is that it has no basis in their Amended Complaint. Nowhere in the Amended Complaint do plaintiffs allege that The Huffington Post represented that their work was purely for public service or that The Huffington Post would not subsequently be sold to another company. To the contrary, plaintiffs were perfectly aware that The Huffington Post was a for-profit enterprise, which derived revenues from their ubmissions through advertising. Perhaps most importantly, at all times prior to the merger when they submitted their work to The Huffington Post, plaintiffs understood that they would receive compensation only in the form of exposure and promotion. Indeed, these arrangements have never changed.

The case puts me in mind of the observations of a great American writer:

Tom said to himself that it was not such a hollow world, after all. He had discovered a great law of human action, without knowing it – namely, that in order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain. If he had been a great and wise philosopher, like the writer of this book, he would now have comprehended that Work consists of whatever a body is obliged to do, and that Play consists of whatever a body is not obliged to do. And this would help him to understand why constructing artificial flowers or performing on a tread-mill is work, while rolling ten-pins or climbing Mont Blanc is only amusement. There are wealthy gentlemen in England who drive four-horse passenger-coaches twenty or thirty miles on a daily line, in the summer, because the privilege costs them considerable money; but if they were offered wages for the service, that would turn it into work and then they would resign.

In an earlier time, I think Ms. Huffington would rarely have been required to lift a paintbrush.

by Lee Gesmer | Oct 1, 2010 | Employment, Noncompete Agreements

While the debate over whether Massachusetts should adopt a law restricting the enforceability of non-compete agreements rages on (well, at least among a group of maybe 100 economists, lawyers and business people), California proudly observes that noncompete agreements are unenforceable in that state (except under very limited circumstances). And, economists argue, that is one reason why the high-tech industry in Silicon Valley is more successful than its counterpart Massachusetts.

Now, come to learn, things were not quite what they seemed. I’m sure that 99% of California companies are in fact impacted by the California law — that is, they cannot impose covenants not to compete on their employees. But a few companies — Google, Apple, Pixar, Adobe, Intuit and Intel — figured out an end-run around this law. Apparently, the Federal Trade Commission tumbled to the fact that each of these companies agreed, with one or more of the others, not to solicit that company’s employees. For example, according to the FTC Apple and Google put each others employees on “Do Not Call” lists.

(more…)

by Lee Gesmer | Mar 20, 2009 | Employment

The First Circuit has denied Staples’ request that it hear the Noonan v. Staples case en banc, or that it ask the SJC to advise it on how to apply the 100 year old Massachusetts statute which provides that “actual malice” may create an exception to the principle that defamation must be false to be actionable.

I posted on this case a few weeks ago (link here), and commented on the agita it had created in the First Amendment milieu. In fact, a vast number of publishers and First Amendment advocates filed an amicus en banc brief urging the First Circuit to reconsider this decision

Today, the Court denied this request and let its February 13, 2009 decision stand. In an order several pages long, the Court found that Staples had waived any First Amendment challenge to the state law by failing to raise it earlier, and that Staples could not, moreover, cite a case supporting the proposition that the law was unconstitutional. Here are some selective quotes from the Order:

Since its initial brief, Staples has argued under the premise that the term “actual malice” in § 92 means “malevolent intent.” Yet, Staples did not then challenge the constitutionality of such a construction. Thus, the . . . opinion found that it need not consider the issue. . . .

The issue is waived, and the fact that the issue raises constitutional concerns does not save the waiver. . . .

Further, Staples has not shown that the constitutional issue is so clear that the panel should have acted sua sponte to strike down a state statute, without the required notice to the state attorney general. Staples still does not cite a case for the proposition that the First Amendment does not permit liability for true statements concerning matters of private concern.

Nor it is appropriate to now certify the question to the SJC. We have answered the question of state law regarding the proper interpretation of the statute, and Staples has not challenged that matter on rehearing. The question of the constitutionality of that state law under the First Amendment is a federal question, which we could answer without certification.

Staples’ petition for rehearing is here.

It is worth pointing out, as a complement to the Staples case, a recent decision by Massachusetts Superior Court Justice James Lemire, issued on January 14, 2009 in Oropallo v. Brenner. The issue in that case was not defamation, but rather the right to privacy under Massachusetts law. Without going into the facts of the case (which are confidential in nature), the court acknowledged an employee’s “expectation that [certain] details [of her life would] be kept private.” The court stated that there exists a genuine issue of material fact as to whether [the Town] had a legitimate interest in publishing [a document that disclosed this information] to Town employees and volunteers that outweighed [the employee’s] interest in keeping aspects of her personal life from public view.”

Accordingly, the Court held, the case should proceed to trial.

In light of these two recent cases it probably goes with out saying, but of course I’ll say it anyways: employers should proceed with extreme caution with respect to statements they make about employees, lest they risk claims of defamation and/or invasion of privacy. Praemonitus, praemunitus.